It is easy to agree that Eid dishes, such as rendang, opor, gulai, and curry came from Arab or India. If Arab and Indian cuisine, like tharid and korma, are aligned with plates of rendang and gulai, we probably will find it hard to differentiate without tasting them. However, the similarity aspect alone is not enough to validate the assumption that the Eid dish in Indonesia came from the west part of the Indian Ocean without a fight.

There are a lot of questions that can brush off the presumption. For instance, from all foreign influences received by the people in the Indonesian Archipelago, why should the dishes from Arab and India–which have a limited population today–become Eid dishes for most Indonesians? The similarity between our dining tables and dining tables in Mumbai and Baghdad is undeniable, but how did the serving process come to us if they really came from there? Last but not least, according to Anthony Reid, the primary protein source of Southeast Asians is fish, so why do we compete to buy meat prior to Eid and give rise to the increase of price?

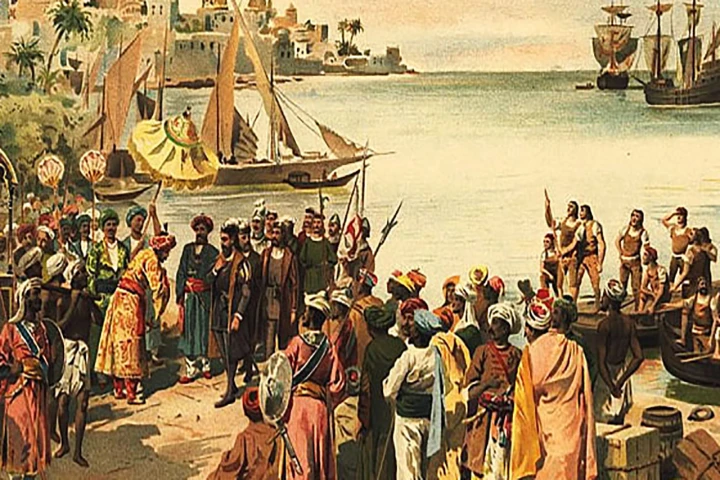

The writing sees the Eid dishes as the remaining piece from our collective memory about the prosperous period of the Spice Routes maritime trade in the 15th and 16th centuries. As time went by, the story was erased, and only the cooking recipe remained. Rendang, opor, and gulai, which are often served during Eid, become a sign that curry-based foods, especially meat-based foods, are special dishes in Indonesia, for they came from the prosperous period which brought many unshakable fundamental changes until today.

Memories from the Prosperous Period

The Spice Routes not only demanded the Europeans to control the fertile lands in Asia but also blessed the Asians with prosperity. Since the 10th to the 18th centuries, the maritime part of the Spice Routes in the Indian Ocean was enlivened by the Muslim traders' trade network, which was firm and brought prosperity. So prosperous that Jack Goldstone (2009:4) called the area the center of the world at that time.

The Eid dishes, like opor, curry, rendang, and gulai include in a type known as a curry that, according to Kirti N. Chaudhuri (1990: 173-174), is a typical dish of former trade cities and Muslim Kingdoms in this route. The close contact between the people could create a similar taste towards the foods. Curry is a thick soup dish made by stir-frying the spice seasoning, putting the meat into it to be slightly fried with spices, and then it will be dissolved with a lot of water and thickener. The thickener is varied in every area. In Africa, it's usually chickpea powder; in North India and Arabian Peninsula, it's milk or yogurt; and in South India and Southeast Asia, it's coconut cream.

People in the Indian Ocean had close contact in trade relations for a long time because they combined two supporting facilities that were not available in other places in the world; they were monsoon winds and Islam. Monsoon winds had long been a natural sailing facility in the Indian Ocean. Recurring each year, it made the sailors in the Indian Ocean use this wind power to depart and go home, provided that they adapted to the wind cycle. Therefore, they used to stay for a long time in a certain place or traded around to many places depending on the wind directions (Lombard, 2005: 32). Besides, the monsoon winds also formed a peaceful trade relationship. The close contact for centuries made the trades not be based upon the spirit to dominate. Instead, they depended on one another (Lombard, 2005: 5). Each area had its mainstay commodity, like clove and nutmeg from Maluku, pepper from India, Aceh, Banjarmasin, Banten, rice from Java, Sulawesi, and Siam cotton from India, cinnamon from Srilanka, and porcelain from China.

With the help of monsoon winds, the maritime trade had existed for a long time, but it became more alive since the entry of Islam's influence. Islam was very supportive towards the trade compared to the previous religions (Risso, 1995:5). In Hindu and Christian doctrines, traders and religious leaders were two different groups; they even had conflicting interests. If traders tended to respect or didn't even hesitate to humble themselves in front of foreigners for the sake of smooth business, religious leaders tended to underestimate foreigners. When meeting foreigners, what made the main motive of the religious leaders was to make them followers. Meanwhile, it had a big potential to offend prospective business partners. On the contrary, there was no significant separator in Islam between traders and religious leaders.

In the Indian Ocean's case during the early modern centuries (the 15th to 18th centuries), a Muslim trade was often a religious leader and a scholar. Even the Muslim's great leader, Muhammad, was also a trader (Czarra, 2009: 40). The trade cities' establishment on the north coast of Java in the 15th and 16th centuries was also initiated by the figures and traders and religious leaders (Ricklefs, 2001: 80-95).

Islam traders possessed an essential role in the culinary culture exchange and new cultural creation, like in the case of curry. The early modern period was when the traders in the Indian Ocean had a marvelous privilege. According to Engseng Ho (2006: 100), the Indian Ocean was a transcultural space consisting of strong Muslim countries which communicated to each other well so that the Muslims, in general, could travel and work freely and safely. This climate became the prolific space for the curry to grow.

According to Elizabeth Collingham (2006: 27), curry emerged in the north of India around the 11th century. At that time, the ruler of the Mughal Sultanate, who was of Persian-Mongolian descent, brought his love towards his ancestor's cuisine to the Indian Subcontinent. Curry emerged from the mixture of meat stew and milk from the north and spicy spices from the south.

Collingham's theory was a special case in India, but the curry was growing wider. There's also a dish similar to Persian meat stew in the Arabian Peninsula called hawamid. Hawamid is a group of middle-aged Arabian food that can be interpreted as a sour stew. They made it by stewing meat and vegetables into thick solution yogurt or milk (Lewicka, 2011: 191). A particular type of hawamid, like tharid, which became Prophet Muhammad's favorite dish, commonly used a bit of cinnamon. After the economic bomb of the Abbasiyah dynasty in the 9th century, especially in the Muslim cultural center in Baghdad, evidence of tharid recipes, which consisted of more spices, was found (Fredman, 2007: 139-149).

At the same time, in the east end of the Indian Ocean, the people used to eat spicy foods but weren't used to eating meat, especially ruminants or red meats. According to Anthony Reid (2014: 37), the protein source of the people in Southeast Asia was fish. They were surrounded by water in Southeast Asia, so it was effortless for them to get fish. Meanwhile, they must hunt in the woods to get red meat or birds. The grazing, which allowed the abundant meat supply like in Arabia, Central Asia, and Europe, could not be conducted in Southeast Asia, for they did not have a vast pasture. Because it's hard for them to get meat, people in Southeast Asia treasured meat and ate them only on feasts (Reid, 2014: 38).

When several parts in this area, especially both sides of the Strait of Malacca, began to enter the Muslim trade network and followed Islam in the 13th century, they developed their version of curry using red meat. The earliest evidence of rendang was found in Hikayat Amir Hamzah in the 16th century (Hanifah, 2017). In the 18th century, an English explorer named William Marsden (1811: 62) said that curry had become a common cuisine in Sumatra.

Interestingly, the curry wasn't only served on special occasions, although it was made of meat. Rendang, for instance, was the traders' daily menu. The dried cooking technique made it long-lasting and suitable as the sailing supply. The trading activity growth had triggered the growth of the cities, which gave rise to new businesses, such as farms (Reid, 2014: 40). With this, the growth of trade in the Indian Ocean clearly prospered the involved people. The Arab traders were led to be able to consume more spices, and the people of Sumatra were used to eating meat, for they were more connected and more prosperous than before.

Curry developed into a trend among all the culinary cultures in the multicultural landscape of the Indian Ocean, for it was a culture from the early Muslim trade hubs, which were Arab and India. The Arabic traders had sailed to the corner of the Indian Ocean since the Islam influence wasn't strong. In the 9th century, many Arab traders were found in Kanton (Lombard, 2005:23). In the 11th century, India, which Mughal dominated, also became a prominent Muslim economic and political power in the Indian Ocean. Meanwhile, the trade hubs in Africa, the Bay of Bengal, and Southeast Asia emerged after the 13th century (Ho, 2006: 100). When these people entered the Muslim trader community in the Indian Ocean, something happened that Felipe Fernandez-Ernesto (2002: 138) called cultural magnetism. The newcomers witnessed the culture of their ancestors as a superior thing and started to replicate it.

Surviving through the Tough Period

The prosperity of the Indonesian Archipelago in the 15th and 16th centuries rarely recur for all areas until today. The same prosperity level also hasn't been able to recur to many of the former trade hubs in the Indian Ocean. Tragically, the majority of the trade hub countries have become a part of the third world countries in the Western Orientalist perspective. The difficulties in the former world economic centers resulted from the disturbance from the European trade syndicate and colonialism in the 19th and 20th centuries. However, curry proves itself as a strong cultural heritage, for it managed to survive today.

The profitable trade relationship ended in the 17th century in the Indonesian Archipelago (Reid, 2015: 312-313). In the 17th century, VOC started the spice monopoly and systematically destroyed the remaining trade network to secure the monopoly. Species were the moving trade commodity in the Indian Ocean. Although there were other commodities, spices were the most precious ones. Behind the clove and nutmeg prices that rose many times from their native land in Maluku to the places where they were consumed, up to thousands of intermediaries benefited from it. The VOC monopoly cut out the intermediate chain so that all the profit from the purchase price difference in Maluku and the selling price in Europe belonged to them.

To secure their monopoly, VOC conquered Sunda Kelapa, Malacca, Makassar, and Banten in the 17th century and all the coastal cities along the North Coast of Java in the 18th century. Since 1677, VOC forbade foreign traders, except for the Chinese, to berth at the dominated ports (Nagtegaal, 1996: 48). The glorious era of the trade network in the Indian Ocean eventually disappeared altogether.

The European trade company aggressions developed into official colonialism in the 19th century. Unlike the VOC period, the Dutch, as the mother country, claimed to have a legal foundation to conduct an extraction systematically. The colonial period was when they made Indonesia a buoy where the Dutch stepped on to prevent them from drowning. During colonialism, massive exploitations brought drastic changes to nature and the demographic of the Indonesian Archipelago.

In my opinion, the most significant impact on the cultural development in Nusantara that occurred during the colonial time was the population growth. According to Jan Breman (via Boomgaard, 1989: 1-2), the population growth rate during the 19th century in the Indonesian Archipelago was 1,6%. The number was far from the world average, only 0.5%, and Asia, only 0.4%. According to Clifford Greetz (1983), the population growth was caused by the indigenous people's workload increase by the labor exploitation from the colonial government. Because they had to work doublessly without any proper compensation, they had many children to lighten up the work. Because it was based upon the will to compensate the workload without the growth revenue, the total population surpassed the food availability. That's why along the 19th century, there were a lot of famines and plague. The colonial government then took responsibility by promoting the extra carbohydrates cultivation, like cassava, but it didn't apply for the protein and vitamin sources (Boomgaard, 2003: 585). Since the colonial era, evidence of the increase in beef intake was found, but the reason behind it was the rise of the European population in the Indonesian Archipelago (Rahman, 2016: 77).

The colonial period was the collapse of the nutritional balance of the indigenous people. From the historical sources collected by Anthony Reid (2014: 55), the Javanese and Southeast Asians were commonly in great nutrients in the 15th to 17th centuries. Their height was even the same as the Europeans. The situation didn't collapse right away during the VOC period. Although it destroyed the economy in many places, the destruction brought by VOC wasn't enough to destroy the nutritional balance, except in the place where they took action as absolute as a country, like on the North Coast of Java. In the traveler's report, such as Thomas S. Raffles, John Crawfurd, W. H. van Ijsselddijk, and M. Waterloo, Yogyakarta, which the VOC didn't dominate, was pictured as prosperous and anti-hunger in the early 19th century (Carey, 1986: 65-67). They, however, strongly highlighted the fate of the Javanese under the sultanate, different from their neighbor in VOC's area, which must endure the heavy extraction load. Because the colonial state power was more evenly distributed than VOC, we can imagine the saddening situation on the North Coast of Java expanding to the entire Dutch East Indies.

In this challenging situation, the curry was preserved by the cultural institution heritage of the peak period of the Indian Ocean's trade, namely the Islam kingdoms and Islamic celebration. Although the Islamic kingdom had lost its political and economic functions, it kept doing its cultural function. Therefore, although the decrease in prosperity made curry no longer consumed widely, its existence in the royal kitchen was everlasting. For instance, ikan masak kering kayu [wood dried fish], which formerly was a supply at the sea, like rendang which later became the special dish of Ternate Sultanate (Tajudin dkk., 2015: 14). For the public, curry formerly functioned as daily food, and then it shifted into becoming a special food that is only served in celebrations, such as Eid al-Fitr, aqiqah, and weddings. Korma curry from West Sumatra, which is very similar to India's korma, is specifically served for aqiqah (Tajudin dkk., 2015: 56). The fall of the Indian Ocean's trade also ruined the coastal community that traders dominated as the primary curry consumer. The significant Muslim port countries, such as Aceh, Banjarmasin, and Banten, changed their orientation into developing crops when the trade was disturbed by the VOC's monopoly (Reid, 2015: 347-348). Eventually, the curry was adapted into the old culture of Southeast Asia to consume meat on special occasions. The Indonesians' interpretation of the special dish from the pre-Islam period, which merely included meat without caring about how to cook it, turned more specifically into meat cooked with curry. The community considers curry from the Indian Ocean trade period special, for they are still Muslims and respect the local kingdom.

Islam's survival was supported by the Duct colonial style, which didn't intervene in the cultural and religious affairs too much, unlike the Spanish and Portuguese. The Catholic religion had a strong basis and became the majority in the Philippines because of the Spanish influence. So did the Portuguese; they tended to mingle with the community in the conquered territory. Further, the Tugu community, whom the Dutch brought from the Portuguese colony when placed in Batavia, became a standout community and culturally different until today. Meanwhile, in the Dutch colonialism case, only few people were influenced by the Dutch culture (Lombard, 2008: 94-127). Islam has remained the Indonesians' majority religion since the trade period of the Indian Ocean until today.

Curries came out and were known by Indonesians from the preservation sites in the royal kitchens and the special recipes among families in Sumatra in the past few decades. The historical culinary sources are rare and unsustainable to be able to be arranged as a complete history as a chronic from time to time. Nevertheless, apparently until the 20th century, curries still became a dish that was commonly found in Sumatra compared to other areas. The development of the types of curry, including opor, rendang, and gulai to become the national Eid al-Fitr dish happened during the independence. After Indonesia was formed as a country and the economy began to improve, the community movement from one place to another nationally became more massive. They were especially sucked in by the economic center like Jakarta so that in this melting pot, rendang, opor, and gulai first became the National Eid al-Fitr dishes.

Closing

Through the curries served during Eid al-Fitr, we can see that Islam, the most influenced religion in Indonesia, was obtained from Indonesia's active engagement in the Indian Ocean's trade network. Indian-Arab culinary culture became a trend in the Indian Ocean because they were influential traders in this place. The network bond of Muslim traders is solid, formed and spread in different parts of the world.

The notion of curry as the national dish from Sumatra happened when Indonesia was newly independent, and can, of course, be easily dismissed. Especially when it is seen from the global perspective by tracing the Spice Routes, we will understand how, through the curry, we are a part of the world center in the 15-16 centuries.

_______

Bibliography

Boomgaard, Peter. (1989). Children of the Colonial State: Population Growth and Economic Development in Java,1795-1880. Amsterdam: Free University Press.

____. (2003) “In the Shadow of Rice: Roots and Tubers in Indonesian History, 1500-1950”. Agricultural History, Autumn, 2003, vol. 77, no. 4: 582-610.

Carey, Peter. (1986). “Waiting for the „Just King‟: The Agrarian World of South-Central Java from Giyanti (1755) to the Java War (1825-1830).” Modern Asian Studies. Vol. 20, No. 1. p.59-137.

Chaudhuri, Kirti N. (1985). Trade and Civilisation in the Indian Ocean: An Economic History from the Rise of Islam to 1750. Cambridge: University Press.

Collingham, Elizabeth M. (2006). Curry: A Tale of Cooks and Conquerors. New York: Oxford University Press.

Czara, Fred. (2009). Spices: A Global History. London: Reaktion Books.

Fernandez-Ernesto, Felipe. (2002). Near A Thousands Tables: A History of Food. New York: The Free Press.

Fredman, Paul. (ed.). (2007). Food: The History of Taste. London: Thames and Hudson.

Geertz, Clifford. (1983). Involusi Pertanian: Proses Perubahan Ekologi di Indonesia. Jakarta: Bhatara Karya Aksara.

Goldstone, Jack. (2009). Why Europe? The Rise of the West in World History, 1500-1850. New York: McGraw Hill.

Hanifah, Hana. (2017). Rendang, merantau, dan Minangkabau: relevansi masakan rendang dengan filosofi merantau Orang Minangkabau. Bandung: Bitread.

Ho, Engseng. (2006) The Graves of Tarim Genealogy and Mobility across the Indian Ocean. California World History Library 3. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Lewicka, Paulina B. (2011). Food and Foodways of Medieval Cairenes: Aspects of Life in an Islamic Metropolis of the Eastern Mediterranean. Leiden and Boston: Brill.

Lombard, Denys. (2005). Nusa Jawa: silang budaya : kajian sejarah terpadu. Bag. 2: Jaringan Asia. Jakarta: Gramedia Pustaka Utama : Forum Jakarta-Paris : École française d’Extrême-Orient EFEO.

_____. (2008). Nusa Jawa: silang budaya : kajian sejarah terpadu. Bag. 1: Batas-batas Pembaratan. Jakarta: Gramedia Pustaka Utama : Forum Jakarta-Paris : École française d’Extrême-Orient EFEO.

Marsden, William. (1986). The History of Sumatra. Singapore: Oxford University Press.

Nagtegaal, Luc. (1996). Riding the Dutch Tiger: The Dutch East Indies Company and the Northeast Coast of Java 1680-1743. Leiden: KITLV Press.

Rahman, Fadly. (2016). Jejak rasa Nusantara: sejarah makanan Indonesia. Jakarta: Gramedia

Reid, Anthony. (2014) Asia Tenggara dalam Kurun Niaga 1450-1680 Jilid I: Tanah di Bawah Angin. Jakarta: Yayasan Pustaka Obor Indonesia.

_____. (2015). Asia Tenggara dalam Kurun Niaga 1450-1680 Jilid II: Jaringan Perdagangan Global. Jakarta: Yayasan Pustaka Obor Indonesia.

Ricklefs, M.C. (2001). Sejarah Indonesia Modern, 1200-2004. Jakarta: Serambi.

Risso, Patricia. (1995). Merchants and Faith: Muslim Commerce and Culture in the Indian Ocean. Oxford: Westview Press.

Tajudin, Qaris, dkk. (ed.). (2015). Antropologi Kuliner Nusantara: Ekonomi, Politik, dan Sejarah di Belakang Bumbu Makanan Nusantara. Seri Buku Tempo. Jakarta: KPG.

_______

The article is the second winner’s work from the Spice Routes writing competition 2021. The article has gone through an editing process for publication purposes on this page.

_______

Yuanita Wahyu Pratiwi is a history researcher. From Bekasi, West Java. A student of Colonial & Global History Leiden University

Editor: Doni Ahmadi

Translator: Dhiani Probhosiwi

Image: ismedhasibuan/depositphotos