“I am turmeric who rose out of the ocean of milk when the devas and asuras churned for the treasures of the universe. I am turmeric who came after the nectar and before the poison and thus lie in between.”

(Mistress of Spices. Chitra Banerjee Divakaruni)

A story told that a woman named Tilottama was able to hear the voices of spices, like the singing of a pinch of turmeric powder above. She was the Mistress of Spices who came from a small island far away in the middle of the sea. With her power, Tillotama shared the ancient secrets of her ancestor in concocting spices into the middle of the modern community of India and America.

Tilottama is a fictional character created by Chitra Banarjee Divakaruni, an Indian author, in a novel entitled the Mistress of Spices (Gramedia, 2003). In this novel, Divakaruni’s endeavor to correlate spices with her birthland, India, was clearly discerned. That “But the spices of true power are from my birthland, land of ardent poetry, aquamarine feathers (Divakaruni, 2003: 13)”. That every spice that is known by the society verily owns a mystical power, “even the everyday American spices you toss unthinking into your cooking pot (Divakaruni, 2003: 13)”, but the only ones to know the secrets were those whose birthland was the Spice Island.

In other words, through this novel, Divakaruni tried not only to strengthen the relationship and power of India upon spices but also voiced out the stories of spices from the part of the world that has been silenced and left out the whole time. The part of the world where the spices were from, in this case, India. So, what about Indonesia?

Spice: The History and Its Story

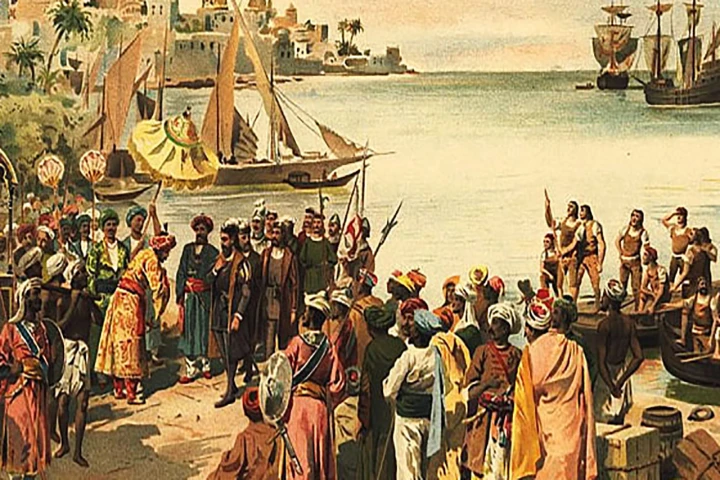

Spices came to humans through nature's gift. While to the world, they came through the hands of traders, explorers, and writers, be it novelists, poets, archaeologists, academics, philosophers, experts or scientists in botanic, economic, or politics, especially the Europeans. The arrival first existed in a story, both orally and written. That's why the thousands of years of spice history actually began from a simple thing: a story.

Indeed, to make the history of spices book as thick as we know today, more than one, even numerous stories were needed. Ironically, the stories didn't come from the first party, the initial owners of the spices and the inhabitants of the Spice Island. Instead, it came from a complete foreign third party, both in front of the spices and the plants' native land.

The reliable first story about spices, especially cloves, that the world could believe and hear, came from an ancient reference as a heritage of the Han dynasty in China (206 BC-220 AD). As told by Jack Turner in Spice: The History of Temptation (2004), the story of "nail spice" was told, which was often used to freshen the palace guests’ breath, who wanted to meet the emperor. The spice was called a clove.

The story of cloves also spread from the Suriah desert around 1721 BC. The story told about a discovery of a handful of cloves in the pieces of burnt ceramics in the ruins of a burnt house owned by Puzuruum (Turner, 2011: xix). The story was made and spread by a group of archaeologists who visited the barren village of Puzurum in Suriah and scavenged the sooty soil in a house until they found the exceptional spice.

Among the time lag of the birth time of both stories above, many stories about spices arouse from the mouth ad hands of the gallant, clever, and brave people, who were vigorously, bravely took action, speculated, and imagined about the spices. Most of them were people who had never seen even a grain of spice yet dramatically told stories of their first meeting with this type of plant. Like Christopher Columbus, who used his finding of cinnamon, that turned out to be mere tree bark.

Other storytellers couldn't even imagine the shape of the native land of spices but borrowed from the bible about the alluring and appealing paradise image. It went too far because aside from imagination, they also borrowed God's name to undergo the search, loot, and exploration of the native land of spices: the tropical islands in another part of the world, which later they called the East. These kinds of people who later made a big stage for spices brought them to the top and introduced them to the world.

According to Edward Said (1994), orientalism was a way to understand the Eastern world based on the particular place in the experience of the European Western people. As a part of the Eastern world, spices kept an orientalism imagination in their history. The image attached to them was not different from the image of the Eastern world in the eyes of the Western world. Something exotic and fantastic as well as mystical. The exotic and mystical images of spices still survive today.

Meanwhile, in the trade field, although they came late, the European Western people were able to show the domination of the spices more than what the Chinese and Arab traders did centuries ago. Equipped with the hand-made maps, they claimed to be the route opener into the spice sources in the East. Armed with galleon and cannon, they dominated spices and the trade route, along with the land and all the inhabitants. Eventually, with all the existing authority and by dint of the intellectuals' support, they composed the history book which placed spices, especially clove, nutmeg, and pepper, on the highest and most significant position that humans had ever given to plants. A position as the face of the world's changer, but with one note. A note about the meritorious ones upon all this and the ones who gained eternal reputation besides spices are the Westerners.

The Voice of the Spice Islands' Inhabitants

The orientalists tended to wish to filter anything from the East for the Western world, including spices. The strategy that was applied for centuries clearly made the whole world, including us, ignore the inequality in spices' history.

The pieces of the spice history recorded clearly that all the stories served there, about spices and the trade, came from the Europeans' mouths and hands. Also, all the appraisals, images, and sins of spices were made from the Europeans' perspective. Further, in the spice history issued in the modern era, the blemish is clearly displayed, and it's as if preserved on purpose with an Orientalist's reason, "...partly on account of my own linguistic limitations, but also in deference to what might be termed the law of increasing exoticism (Turner, 2004: 24)."

On the world stage, spices were expected to introduce themselves as the Eastern world's commodity, but oddly, not by using the people's voice from the East, but from the Western's instead. Spices were never accompanied by the farmers who cultivated or the community who directly shared their lives with them, let alone the little people who suffered because of them. This is the Western way to make spices exotic.

The stories of spices heard by the world seem always to be full of beautiful memories, great adventures, and the splendor of the past, epic and mysterious. In those kinds of stories, only two figures are allowed to be shown: hero and monster. The two characters represent the clear binary opposition: white and black. In the case of spices, the Europeans are clearly the heroes, while the actual owners of spices are the monsters—it includes us, who live in the Spice Islands, Nusantara.

As a small dot on the modern world map, borrowing a piece of Turner’s narration, the European explorer’s view on what he witnessed in North Maluku in the early 16th century seemed so natural instead of an insult: “... [the inhabitants are] like beasts… so stupid that if they wished to do evil they would not know how to accomplish it (Turner, 2004: 67).”

A Portuguese historian, Joao de Barros (1496-1570), had the same opinion about the island: “ill-favoured and ungracious… the air is loaded with vapours… the coast unwholesome… [the islands] a warren of every evil, and contain[ing] nothing good but the clove tree (Turner, 2004: 67).”

Ignoring their stupidity about spices and bad morality, the strafe of the kind of stories excluded the role of parties that closely and directly related to spices. There is no true voice of the Spice Islands' inhabitants in the history of spices. In the spice trade, the spice producers had to work extra hard to write their names in a noble position, although the area had been a part of the route for hundreds of years, as experienced by our land, Nusantara.

Literature and an Attempt of the Spice History Reconstruction

As known by the world, the history of spices is clearly Western-oriented. However, history is not static. Giambattista Vico, an Italian philosopher and historian, realized that history always develops. The flow can be changed. Through his observation, Vico also believed that humans are the ones who create their history, that everything they can perceive is what they have done (Said, 1994: 6). It means that all the obscurity recorded in the history of spices page is open to be criticized and reconstructed, especially in the most significant yet excluded part. The part where the Spice Islands inhabitants testified. Literary work is one of the ways to reconstruct this.

Literature is like a mouthpiece for the humanities. The fictional texts can give a new perspective about life and reflect the social reality around it. Besides, a literary work is also a very rich source for human experience. It's not a mere text that offers a story, but it gives information about something and shares human perspective, experience, understanding, and thought. It can fill the void and move and influence, as many European classic works managed to prove.

Although located in the eastern part of the world, Indonesian literature can compete with western literature. Our literature has many remarkable authors and works that can compete, both on national and international stages. As a prosperous country, our literature is colorful and fits the authors' background. Of all the diversity, there are a number of literary works which tell stories about spices. Three of them are Mirah dari Banda (2010) written by Hanna Rambe, Kura-kura Berjanggut (2018) written by Azhari Aiyub, Haniyah dan Ala di Rumah Teteruga (2021) written by Erni Aladjai.

Kura-kura Berjaggut is a novel that will take the readers on an adventure to the glorious periods of spices. An explorer named Ujud wanted to take revenge on Sultan Nuruddin from Bandar Lamuri, who had killed his family. Ujud tried to win the Sultan's trust, so he managed to become a spy who had a job to spy the movement of spice traders and pirates' vessels. An essential position that made him easier to take revenge on the Sultan.

By the author, Kura-kura Berjanggut was proposed to fill the empty page in the spice history about what happened to Lamuri Kingdom in the 16th century and Aceh in the 19th century. Taking palace in Aceh, which was once famous as the trade hub and the most remarkable pepper producer globally, the novel offers its perspective in seeing spices. That by dint of pepper, a son of a slave can be a king, massive extermination happened, a sultan was born, and many villagers had to lose their lives. That behind the exotic aroma of spices, there was the smell of blood, rotten smell of betrayal, and fierce revenge.

Meanwhile, the novel Mirah dari Banda tells a life drama of a woman named Wendy Higgins, which began at the nutmeg plantation in Banda Islands, Maluku. A place where she met an old cook named Mirah, who lived a miserable life in the past. In the colonial era, Mirah was a slave in the Dutch nutmeg plantation, who was later made into a bride to dedicate her life to her foreign master, the master colonizer. During the independence period, she was a grandmother who lived alone since the Japanese soldiers took her daughter and war killed her grandson.

Clearly, Mirah dari Banda pictured the misery of the people in the Spice Islands, and it was never recorded in the history of spices. The misery which was caused by spices, which left scars and deep trauma that is hard to erase and was even passed down from one generation to another. The novel raised a question about what happened in the Spice Islands after the foreign explorers found the place; what was buried under the European colonizers' shoes when their ships stood up straight in the spice trade's peak of glory; who were the ones sacrificed for the glory of the Western world? The answers to all these questions are on the Spice Islands' inhabitants' tip of the tongue. That the Europeans turned spices into blessing and curse at the same time, for the people who planted them: they were disarmed and burnt down just like what the Dutch did to the people of Banda Islands, before they were later crammed into the new page of spice history created by Europe as people with low morality and uncivilized.

The novel Haniyah dan Ala di Rumah Teteruga served a story about what happened in the east part of the Spice Islands around fifty years after Nusantara officially aroused as an independent country named Indonesia. On a spice producer island in the East of Indonesia, a mother and her child must fight to face the tough life as a clove farmer. The drama of the people's lives in the small village who lived modestly was ruined not only because of personal and family problems, but also spices.

Haniyah dan Ala di Rumah Teteruga identified spices as two sides of a coin for people who cultivated them. One side is a source of income; the other side is the source of the problem. The novel gave a voice to the clove farmers whose rights were removed for the country's sake, although they lived with cloves from generation to generation. What happened to the island was not far from what their ancestors endured in the colonial era. The government established a monopoly institution of the clove collectors and marketers to supervise and limit the clove trade. They tried to silence the voice of the farmers in many ways. In this novel, spices emerged hand in hand with violence and injustice.

From the explanation above, the importance of the message carried by this kind of literary works is clearly seen. The three of them were able to create awareness about the role of spices in Indonesians' lives, in general, and the spice farmers specifically, more clearly and realistically. The three of them also managed to bring the readers the perfect irony from what is hidden behind the significant chapters of the world spice history. Unfortunately, there are only few Indonesian literary works of this kind. From a long time ago until now, the tendency doesn't change much. From the little thing, be it a novel, poem, or short story, most works are commonly published for the local readers or issued limitedly. Why did this happen?

As a trade commodity, spices had their glorious time in the market indeed—some particular spices are even still considered such. On the contrary, as a story theme, spices are considered less attractive by the book market, furthermore if it's linked to the locality. In the middle of the market, the popular fiction books that are light and have urban settings defeat the popularity of books that relate themselves to spices. The condition influences the number of Indonesian literature with a spice theme that is printed and the interest of our authors to choose it as story material.

Only lucky literary works can shine and attract the readers like two of the three novels above. Kura-kura Berjanggut and Haniyah dan Ala di Rumah Teteruga got a fortune from the award winner labels printed on their book covers. Other writers, especially from Java or those who just searched for a position in the literature world, must struggle hard to offer the kind of work to the publisher and public. At this point, Indonesian literature needs support from the government and vice versa.

Since the government initiated the Spice Routes program to strengthen Indonesia's position as the world maritime axis in the last two years, support from all the people is needed. In addition, the Spice Routes' collective reconstruction and revitalization effort in all fields, including literacy or literature.

If the Eastern people were unable to speak, so their authority was easily stripped off, today is the time to turn things around. Because since then until now, Eastern cultures and countries have been owning something bigger than what the Western said. We can create a strong narration about our role and position in the history of spices and their trades through literary works. The way is by giving the widest opportunity to Indonesian writers to echo the voices of people who are deserving and suffered behind the glory of the world spices: spice farmers and inhabitants of Spice Islands in Nusantara.

Like Tillotama, Divakaruni's fictional character, we should realize that as the inhabitants of the Spice Islands, we inherit the sheen of spices under our skin since we were born. So, let the sparkle guide us to use all energy and ability to claim what should be ours for a long time: spices and the stories about them. Because the stories of spices are our stories; the spice history is our history.

The Spice Routes will always be a part of us, Nusantara.

***

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Aiyub, Azhari. (2018). Kura-kura Berjanggut. Jakarta: Banana

Aladjai, Erni. (2021). Haniyah dan Ala di Rumah Teteruga. Jakarta: KPG

Divakaruni, Chitra Banerjee. (2003). Penguasa Rempah-Rempah. Jakarta: Gramedia

Rambe, Hanna. (2010). Mirah dari Banda. Jakarta: Pustaka Obor

Said, Edward W. (1994). Orientalisme. Bandung: Penerbit Pustaka.

Turner, Jack. (2011). Sejarah Rempah dari Erotisme sampai Imperialisme. Depok: Komunitas Bambu.

Turner, Jack (2004). Spice: The History of a Temptation. HarperCollins Canada. http://www.harpercollinsebooks.com.ca

_______

This article is the third winner’s work of the Spice Routes writing competition 2021. The article has gone through an editing process for publication on this page.

_______

Anindita S. Thayf is a novelist and essaist, born in Makassar, 5 April 1978.

Editor: Doni Ahmadi

Translator: Dhiani Probhosiwi

Image: TTStock/Twenty20