The discussion about cloves and the spices of Nusantara brings us to the explorations that stretch out into the faraway time and places. Since the early AD, spices had become a trade commodity that reached the Central Asia market, including cloves. Spices’ value and price were high, for they were a multipurpose commodity that people used as medicines, foods, or fragrances.

In the beginning, the Asian traders’ notes from classical Chinese or Indian manuscripts stated that the spices came from a nation in the East, illustrating a location that was difficult to trace. It was mainly caused by the limited knowledge of the origin of the spices. Along with the development of the sea trade routes after the 5th century, the traders became more familiar with the shipping routes that passed through Nusantara, including Sumatra and Java.

In the Chinese note, cloves and Maluku had been written since, at least, the eras of Song Dynasty 宋 (960-1279) and Yuan 元 (1271-1368). The note stated that cloves acted as a gift or trade commodity brought by the traders of Champa, Java, Srivijaya, Middle East, Chila, and Butuan. In a note entitled Dade Nanhai zhi 大德南海志, written around the 14th century, it stated that cloves were among the medicinal essence brought from Guangzhou in the foreign traders’ ship. However, in the Chinese sources, the Maluku Islands appeared later than the cloves..

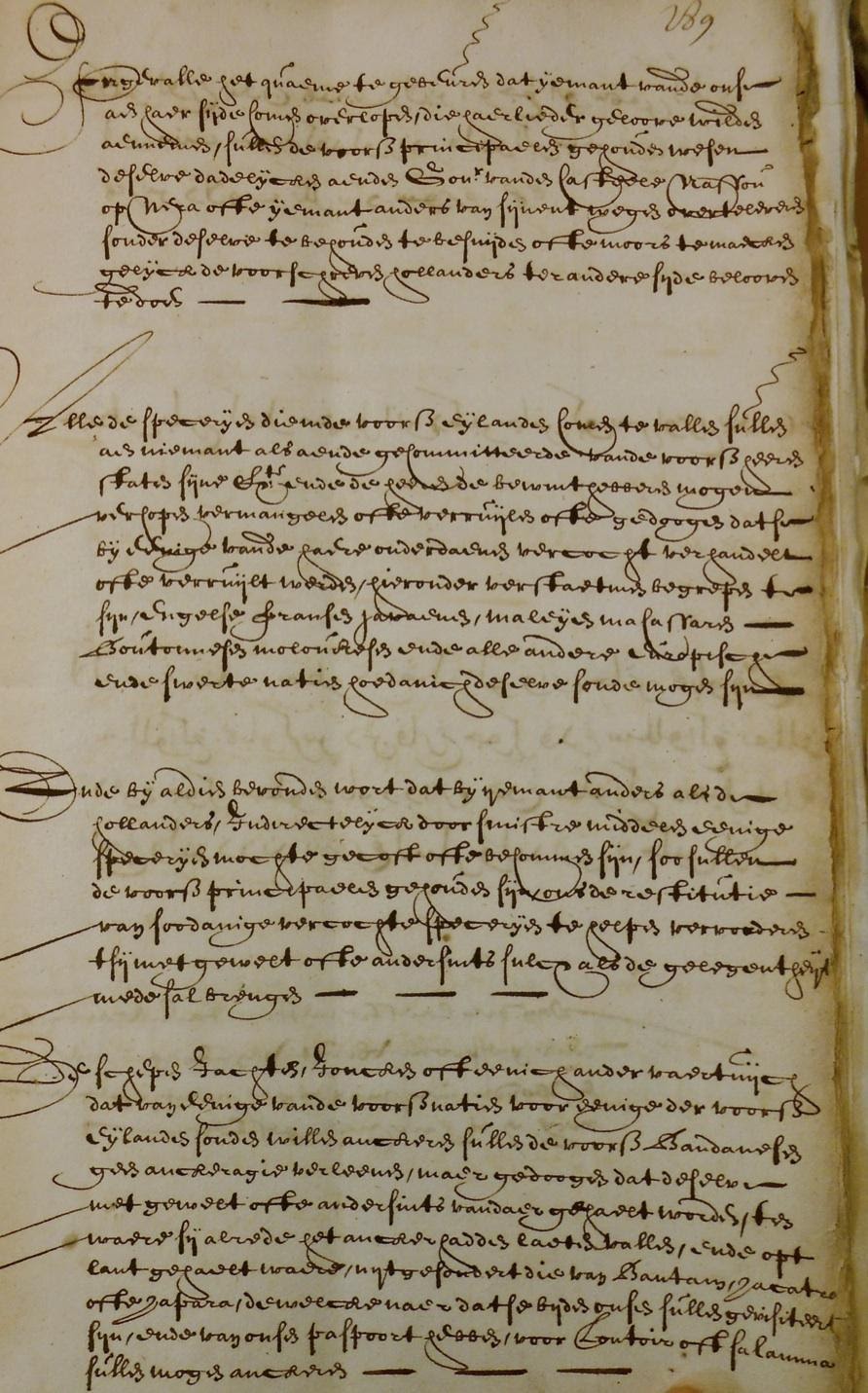

The Europeans who traced the origin of cloves tried to investigate it through the commodity's name. However, they experienced difficulty, for the origin of cloves from the Arabs and Persians was unknown.

Based on its history, clove in Latin is called cariofilum, for the Muslims (Moor) who brought it called the clove Calafur. When the Portuguese and Spanish traders found the native land of clove, the Spanish called it Gilope, for they got the cloves from Gilolo Island. Meanwhile, since the form resembled a nail (clou), the Portuguese called it clou de girofle.

The people of Maluku called it in the Malay language, cengkeh, while the Indians called it lavanga. The variation of clove's names became evidence that marked how influential this Nusantara spices commodity was for the various use of languages and the forming of trade routes called the Spice Routes.

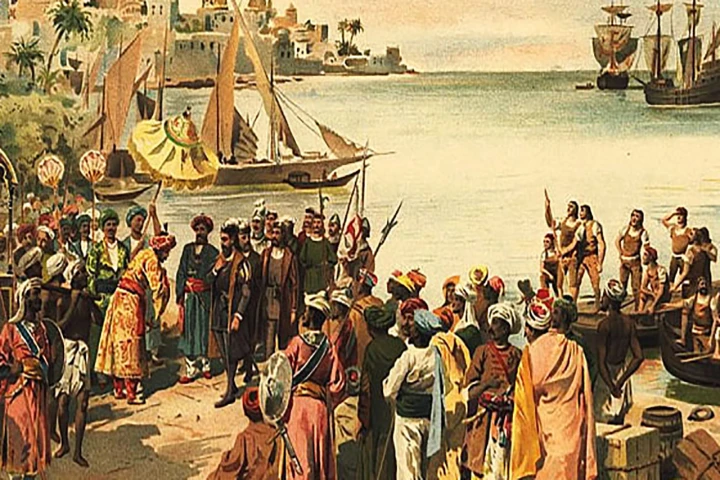

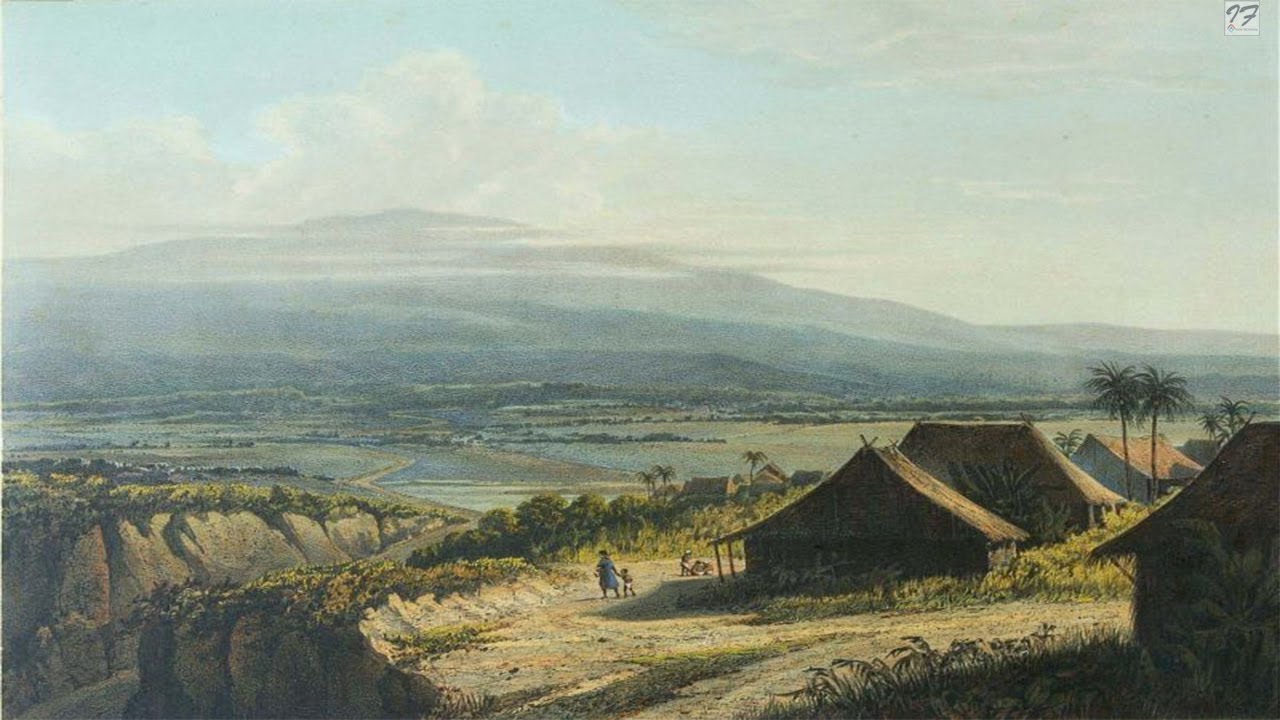

The development of sea trades in the middle age increased the traders' access to reach the native land of the spices. It eventually gave rise to the establishment of ports that started as small and limited ports until they grew bigger and formed cosmopolitan cities with trade networks that stretched along the coast of South Asia, the Bay of Bengal, the Gulf of Siam, and Nusantara. As Islamic kingdoms strengthened near the end of the middle age period, the development of trade cities advanced rapidly, including Gowa, Coromandel, Malacca, Aceh, Banten, and Makassar.

The long-distance traders, such as Gujarati, Persian, or Chinese, and Nusantara traders, including the Javanese, Malay, and Butonese, became the main pillars of the trade cities' network. The distant sea journey forced them to transit in the port cities to rest, waiting for the wind while fulfilling the ships' supplies with clean water.

During the 16th and 17th centuries, the traders who stopped by at the Nusantara port cities, especially Banten and Makassar, bought the rice to be exchanged with spices in the Maluku Islands.

Although the traders commonly stayed in the settlements with the merchant seamen from their native land, the settlements slowly formed a cosmopolitan characteristic in the cities that gave rise to the cultural diversity, especially in the culinary aspect and the Malay language that we can see the traces today.

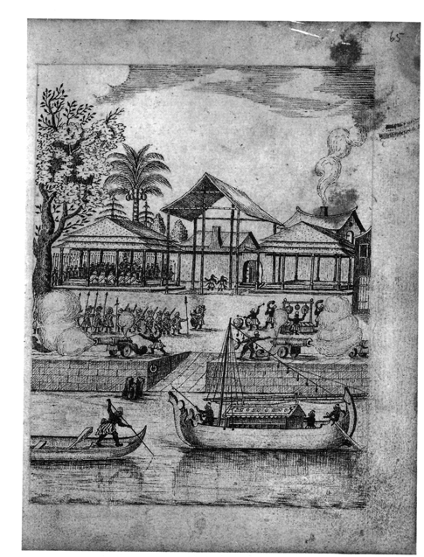

A painting of the Banten Palace gate, created by a Danish in 1676. Copied from the Claude Guillot, “La politique vivrière de Sultan Ageng (1651-1682)”, Archipel no 50, 1995, h. 91.

The Malay language became a significant lingua franca for the traders to communicate. Further, the traders and sailors who were commonly filled with men also formed matrimonies with local women so that they formed diverse families with different origins that created cultural diversity.

The cultural intermingling didn't only happen in Indonesia but also in the Philippines, which gave rise to Mestizo culture. Meanwhile, in the Malay Peninsula and the Peranakan culture (crossbreed culture) emerged in most areas of Nusantara.

Even though we need to remember that the cities were attached to the characteristics that fitted the socio-political system of each kingdom or sultanate, the presence of foreign traders in the ports and markets added colors to the cities with the cultural aspects that they brought. The trade city network was tied by the trade goods, trade ships, sea, and languages. Here is an interesting portrayal of the trade cities' network, the trade cities that could present their uniqueness and at the same time serve the similarity with other trade cities in particular time and space. The portrayal of these coastal trade cities reminds us of the Mediterranean Sea in South Europe and North Africa.

It’s important to note that the presence of Europeans in the spice trade network was relatively later than the Asian traders. The Portuguese traders and travelers were the first to discover the location of spice hubs in the East Nusantara. Their notes became the source of information for other European traders and travelers, especially Spanish, Dutch, and English, to come to Nusantara.

The number of traders that increased did not fit the availability of markets and the demand for spices. It slowly started to take a toll, in which the ruling nation felt the necessity to monopolize the spice trades. It triggered the emergence of many trade cities initiated by the Europeans, such as Manila in 1571 by the Spanish. The Dutch also established Batavia in 1619, and the English did the same thing with Singapore in 1819. It marked the new episode of the spice trade world in Nusantara.

Yerry Wirawan, a teaching staff at the Sanata Dharma University

Text: Yerry Wirawan

Editor: Doni Ahmadi

Translator: Dhiani Probhosiwi