“To Indonesia, the Spice Routes have the potential to be proposed as the World Heritage Cultural Routes. Furthermore, today, UNESCO only recognized the Silk Roads and Qhapaq nan as world heritage.” (Nyoman Suhaida, Coordinating Ministry for Human Development and Cultural Affairs. Kompas, August 18th, 2021).

The Silk Road at a Glance

The Silk Road was formed around 200 years BC. According to Philip D. Curtin (1998) in Cross-Cultural Trade in World History, the land trade route that traversed Central Asia was formed in the 2nd century BC. The route connected China and the Mediterranean. The forming of the land route was followed by the growth of the maritime sailing route, which linked China, the Mediterranean, and Japan. The sailing route continued to develop from the Red Sea, Persian Gulf, and India. In addition, other shipping routes emerged from India, Southeast Asia, China, and Japan, which followed the direction of the monsoon wind.

In ReOrient: Global Economy in the Asian Age, Andre Gunder Frank (1998) wrote that the leading commodities of the Silk Road (land) were silk, gold, textile, iron, and silver. Unlike the land route, the leading commodity for the sea route was not silk but spices. Spices became the leading commodity in the maritime trade route among India, Egypt, and Europe for centuries BC. The spice commodities included pepper and cinnamon from Srilanka. Meanwhile, the maritime route from India to the east until it reached Nusantara and China had not developed well.

According to D.G.A Hall (1988), Sejarah Asia Tenggara [English title: History of South-east Asia], Nusantara Spice Routes began to develop when the conflicts among the kingdoms in Central Asia occurred near the AD era, which disrupted India’s gold trade. It led India to buy gold currency from the Roman Empire. The gold currency trade was later banned by Emperor Vespasianus, who ruled during 69-79 AD, for it had the potential to disturb the economic stability of the Roman Empire. It forced India to find new sources of gold in the Eastern countries. Indian literary works gave quite a lot of information that there was gold in the Eastern country. The gold turned out to be spices, the European’s coveted game. The Indian trade eventually took a new direction to the east.

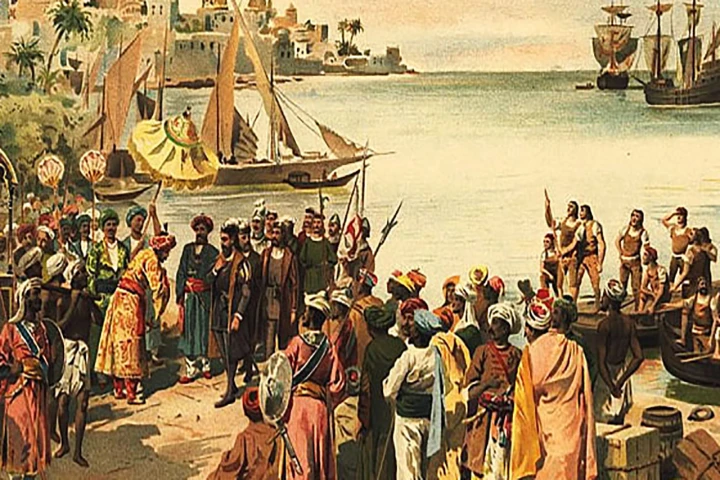

In a paper “The World of Juragan and Nahkoda in the Java Sea Region 1684-1726”, Hendrik E. Niemeijer (2015) stated that Nusantara spices had complete quality and variation compared to those from Malabar India. In addition, the price of the Nusantara spice was only one-third of the Malabar spice price. The Nusantara spice commodity eventually managed to get rid of the spice commodity from Srilanka in the Mediterranean Sea’s trade area in the 1st century AD. When they came to Nusantara, Indian traders brought textile commodities to be exchanged with spice commodities. The barter economy became the characteristic of the era. Moreover, Indian rice was also a bartering tool to obtain spice commodities. The trade relation between Nusantara and India opened Nusantara Spice Routes more widely to be more known by broader nations.

O.W. Wolters (1967) stated that the Nusantara maritime trade route with China occurred in the 5th century AD. According to Wolters, Nusantara sailors possessed the skill to sail to China. It is proved by the numerous writing imprints from Chinese royal officials about the arrival of trade delegations from multiple kingdoms in Nusantara. According to Anthony Reid (2002), approaching the 12th century, the trade relation between Nusantara and China used a lot of Nusantara vessels as a means of transportation.

Andre Gunder Frank (1998) remarked that spices were the leading commodity hunted by traders from China. The spice commodity was often exchanged for silk fabric in goods exchange transactions between the two parties. Therefore, the existence of silk fabric in Nusantara was not the essential commodity hunted by Nusantara traders. Nusantara traders’ primary purpose is to sell the spice commodity to Chinese traders, not buy silk from them. Consequently, the trade relation between China and Nusantara until the 12th century was still dominated by the spice commodity. It led Anthony Reid (2002) to state that the shipping and trade routes in Nusantara are more suitable to be called the Spice Route rather than the Silk Road.

The Earliest Agricultural Science

Nusantara Spice Routes is not an imaginary tale. The wealth of Nusantara spice was the product of the earliest agricultural technology globally. In the book Eden In The East, Stephen Oppenheimer (2010) explained that the well-structured agricultural world in Indonesia was proven to precede the agricultural world in the Neolithic Revolution in the Far East (Russia and the surrounding countries). The sweet potato cultivation in Indonesia has been recorded in 15.000 and 10.000 years BC. The rice cultivation in Thailand was recorded to be 6.000 to 7.000 years BC. The agricultural technology in Southeast Asia is proven to be older than China’s.

An artifact was discovered from the Bronze Age in Ban Chiang (South Thailand) and Phung Nguyen (North Vietnam) around 5.000 and 6.000-year-old. The artifact is much older than the oldest of the Bronze Age in the Near East (the area of Mesopotamia, like Syria, Palestine, and Egypt). It means that it happened before China reached the development phase like this.

Oppenheimer gathered the tale of ‘banjir setinggi gunung’ [‘a flood high as a mountain’] from Sabang to Merauke. Further, Oppenheimer suggested that the tribes in Indonesia’s interior, especially eastern Indonesia, are descendants of those who survived the Ice Age without migrating outside Indonesia. The ancestor only needed to hike to a high mountain peak in some parts of their tale. Some animals played a significant role in the disaster. For example, the inhabitants of Alor in NTT think that a giant sawfish sank the continent and cut it into several small islands.

The people on Seram Island have a story of their ancestor, who was saved from a flood by an albatross who brought them to an island. The people of Toraja also possess a story of a flood high as a mountain, and they saved themselves by climbing the pig’s trough. Dayak Ot Danum tribe in Bariot, South Kalimantan, also possesses a story of the flood which sank a continent except two mountains, and they escaped to the mountains. The Dayak Iban tribe has their version of a figure of Prophet Noah named Trow, who escaped by lesung carrying pets. Therefore, Oppenheimer viewed the story of the flood in Nusantara as original and had existed before Islam and Christianity entered the area. Thus he assumed that Indonesia and the areas in Southeast Asia were a continent that sank in the big flood at the end of the Ice Age.

The roof of Toraja traditional house becomes one of the traditional architectures that are easiest to recognize in Indonesia. The material is Uru, the local wood like teak wood from Java Island. It always faces the north, and the roof bends like a boat. The style of the roof is called tongkonan. Tongkonan depicts a boat used by Puang Barulangi when he sailed to Toraja thousands of years ago. That’s the mythology told by C.F Palimbong, the Head of North Toraja Community Alliance on Tempo, published in Tempo Magazine December 13th, 2010 edition. In mythology, barulangi is believed as the first human created by God in Toraja, coming from the north named Pongko; hence Toraja’s traditional house always faces the north.

According to Oppenheimer, the story of the flood in mythology like in Toraja is one of the fundamentals that the world civilization came from Indonesia (Southeast Asia), especially from Sunda Shelf, that today has sunk into the Java Sea and the South China Sea. Sunda Shelf or Sundaland is an area of wide plains that today is in Indonesia and other surrounding areas. Before being separated by the sea due to the end of the Ice Age around 6.000 years BC, Sumatera, Java, Kalimantan were still one with Mainland Asia. The land also connected Kalimantan with South China.

Oppenheimer believed that before Sunda Shelf sank, the inhabitants possessed the ability of agricultural technology, fishing technology, and earthenware. This agricultural technology is the oldest in the world. There is no record of other communities in other parts of the world who possessed the ability. When the Ice Age’s great flood submerged the Sunda Shelf, the inhabitants escaped and dispersed worldwide. The shipping towards the West brought Indonesian ancestors to Europe. The shipping towards the East led them to the American Continent by traversing the Bering Strait, where thousands of years ago there was still land that could be reached on foot after taking a boat.

Further, Oppenheimer explained that the ancient Sumerian civilization (5.000 BC) was greatly influenced by the civilization of people who spoke Austronesian. Sumeria was one of the ancient civilizations of the Middle East located in the south of Mesopotamia (the southeast of Iraq). Austronesia is a family language covering Indonesian and other languages in Southeast Asia. The earthenware technology in Sumeria was identical to those in Austronesia. The earthenware found in Ur, one of the ancient cities in Sumeria, had similarities to the earthenware technology in the Austronesian civilization, for instance, the red coloring. There’s also the similarity in sculpturing technology by tattoos. In Central Sepik, Papan New Guinea, the native tribes still practice tattoo technology.

Besides technology, Indonesian ancestors also spread flood mythology or tales to the world. The Sumerian flash flood was similar to the flood in the Prophet Nuh’s era. The discovery of the cuneiform tablet in Sumeria gives information about the Gilgamesh flood, which is presumed to be the flood that began from the sinking of the Sunda Shelf in Nusantara during the Ice Age. The myth tells the story of Gilgamesh, who met with Utnapishtim, who claimed to survive the great flood in the east country by taking a boat or big vessel.

Oppenheimer’s writing shows that our ancestors were sailors with the main characteristic of sailing the vast ocean, hitting the wave fiercely, and could go through the storm. Not at all surprising that later the people of Nusantara sailed to different parts of the ocean to trade spices.

The Story of the Spice Routes Decades Before

There is an ironic story. In the past few decades, the interpretation of the Spice Routes feels strange in our own country. It is proven by the publications of books from the Department of Education and Culture of the Republic of Indonesia: Cirebon sebagai Bandar Jalur Sutera, Kumpulan Makalah Diskusi Ilmiah (1996), Ternate sebagai Bandar Jalur Sutera, Kumpulan Makalah Diskusi Ilmiah (1997), and Diskusi Ilmiah Bandar Jalur Sutera (1998).

The books were products of multiple Seaports in the Silk Road Seminar held by the Directorate General of Culture, the Department of Education and Culture, almost every year. It began with the Surabaya Seaport Seminar (1988), Tuban Seaport Seminar (1990), Demak Seaport Seminar (1991), Pasai Seaport Seminar (1992), Banden Seaport Seminar (1993), Sunda Kelapa Seaport Seminar (1994), Cirebon Seaport Seminar (1995), Ternate Seaport Seminar (1996), and the last was Jakarta Seaport Seminar (1997).

The publications of books that put their backs on the Spice Routes by placing the Silk Roads show that the intellectual world was still trapped in the foreign countries’ narratives in a few decades. We forgot to re-read, re-examine, re-analyze, and retake the conclusion of the discourse of Silk Roads that was just labeled on Indonesia. And the narration of the Spice Routes in Nusantara, on the other hand, was neglected.

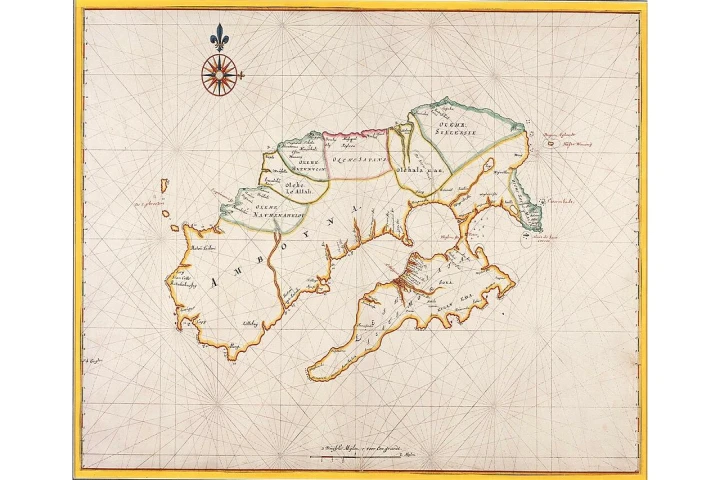

Even that world history remarked that due to the desire to dominate Run Island (Spice Island), the Dutch were willing to exchange it with Manhattan Island, as recorded in the Treaty of Breda on July 31st, 1667 in Breda, Netherlands. The 3rd clause of the Treaty of Breda decided that Run Island in Maluku as the British colony became the Dutch’s. At the same time, Manhattan Island (Nieuw Amsterdam) in America as the Dutch colony was officially owned by the British.

Nutmeg was one of the spice commodities that only grew in the Banda Islands, including Run Island. Traders from Malay, China, and India came to Banda Islands to buy nutmeg to be later sold through the leading port cities, namely Malacca and Calicut. The nutmeg was later bought by Arab traders and brought through the Persian Gulf and the Red Sea towards the Arabian Peninsula and Alexandria. Following this, nutmeg was exported to the European Continent. In the Blue Continent, the price of half a kilogram of nutmeg was equal to seven fat bulls.

National Geographic recorded that the nutmeg price could reach sixty thousand times the purchase price in Banda Islands. Nutmeg was hunted, for it was believed to improve vitality and act as a preserver. Without nutmeg, the noblemen and European bourgeois seemed to merely be eating carcasses and stale foods. When the Byzantine Empire fell, nutmeg vanished from circulation in Europe, for it was hard for the traders to cross Alexandria. The Usmani Sultanate closed the European south gate. The European sailors and their trade syndicates eventually began to search the native land of nutmeg and found it in the Banda Islands.

The Dutch colonial in the Banda Islands was recorded as the most brutal colonialism in world history. The VOC soldiers massacred the native inhabitants of spice islands mercilessly, then from fifteen thousand souls, only six hundred people survived. It was a typical genocide act of the European colonizer which aimed to dominate the Nusantara “gold”.

After the Dutch arrival, the Banda Islands were also visited by another European colonizer from the United Kingdom. England eventually succeeded in dominating Run Island in 1616. With the presence of two colonial kingdoms from Europe, war became inevitable. The battle lasted five years, and the Dutch managed to control 10 out of 11 islands in Banda, except Run Island, which was occupied by the British. In the end, for Nusantara “gold”, Run Island with an area of 6 square kilometers was exchanged with Manhattan Island with an area 18 times Run Island. The Kingdom of the Netherlands succeeded in planting their flag in the entire Banda Islands consisting of Nusantara “gold”, nutmeg.

The Run Island and Manhattan exchange was proof that the world maritime trade route was more dominated by the spice commodity and not silk fabric. No world history record tells the swap of the small island with the big island was a mere intention to control the silk fabric.

As the owner of the Silk Road, China managed to keep its attraction in the 21st century by launching the One Belt, One Road/OBOR program–the reincarnation of today’s Silk Road that glorifies China’s globalization vision. Xi Jinping directly declared the program in 2013 involving multiple nations from Asia, Europe, and Africa. The modern Silk Road covers land and sea routes. The land route starts from East Europe to West Europe. The sea route traverses Vietnam, Malaysia, Indonesia, India. The Silk Road will cross East Africa from Asia, heading to Kenya, Somalia, and traversing the Gulf of Aden and the Red Sea. Following this, from East Africa, it will continue to North Africa through the Suez Canal and heading to Italy.

Yantina Debora (2017) explains that for China, the Silk Road will strengthen financial cooperation and road connection or infrastructure by forming a strong transportation route with another country. Started from China to West Europe and from Central Asia to South Asia. It will help the low economy countries in the Silk Road in infrastructure development. One Belt, One Road aims to strengthen the trade facility by focusing on abolishing trade barriers and taking a step or policy to decrease the trading and investment fees. Also, to enhance policy communication related to economic cooperation.

The route has 3 billion souls of market potential. The maritime Silk Road has around 600 million population in Southeast Asia alone. China is determined, the President Xi Jinping also promises to serve 8 trillion US dollars for infrastructure development in 68 countries. Today, according to China, its party has invested 50 billion US dollars in 20 countries along the Silk Road routes. In a greeting speech in the Belt and Road Forum (BRF) in Beijing on May 14th, 2017, President Xi Jinping decisively stated his notion in front of 100 representatives of countries traversed by the Silk Road. His speech entitled “Work Together to Build the Silk Road Economic Belt and The 21st Century Maritime Silk Road” asserts the Chinese’s sweet promise in this megaproject. “We will contribute to realizing the Silk Road initiative, a project of the century, that will benefit many people in the world,” said Xi, quoted from Xinhuanet.

Better late than never. According to Singgih Tri Sulistiyono (2020), Indonesian historians had just woken up when China inaugurated OBOR in 2013. Various Spice Routes workshops marked the awareness to revive the Spice Routes. The first seminar was Borobudur Writer and Cultural Festival with the theme Reverse Flow: The Nusantara Spice and Nautical Memories between the Colonial and Postcolonial in 2013. Two years later, the National Museum of Indonesia held an Exhibition and Seminar of the Spice Routes Shipping and Trading in Nusantara. In the meeting, an idea to re-read the “Maritime Silk Road” to become the “Spice Routes” emerged, for spices were the main commodity. The process keeps going with the proposal to UNESCO to make the Spice Routes the World Heritage Cultural Route like the Silk Road.

A Story from Within

While waiting for the government to propose the cultural route to be recognized by UNESCO, the effort to ground the Spice Routes for the Indonesians is everyone’s responsibility. In this case, the education world can act as a gate of the Spice Routes knowledge for the young Indonesian generation in reading the roles of Indonesians in world history. The internalization of the Spice Routes through the education world is expected to become an everyday conversation and not a fall short of expectation.

The process doesn’t need to be interpreted with a curriculum change or changing textbooks. Teachers can read books about the Spice Routes to be transferred to the students in classes aligned with the subjects they teach. The knowledge about the Spice Routes can also be distributed to multiple locations by the Ministry of Education and Culture in the form of books for school libraries or reading parks, where the whole thing empties to the belief to realize the Spice Routes literacy movement–a cultural movement where Indonesia played a significant role in changing the world.

_______

The article is one of the top 10 winners’ works in the Bumi Rempah Nusantara untuk Dunia Writing Competition 2021. The article has gone through an editing process for publication on this page. Edited from the initial title “Jas Merah: Jangan Sekali-kali Melupakan Jalur Rempah!”.

_______

Romi Febriyanto Saputro is the Section Chief of the Archives and Library Development, the Sragen Library and Archives Service.

Editor: Doni Ahmadi

Translator: Dhiani Probhosiwi

Image: Alfredo Roque Gameiro