When today you can't differentiate nutmeg's aroma from clove, people will think you are infected with the Covid-19 virus, but if it happened in the 15th century, people would laugh at you, for you would be considered poor.

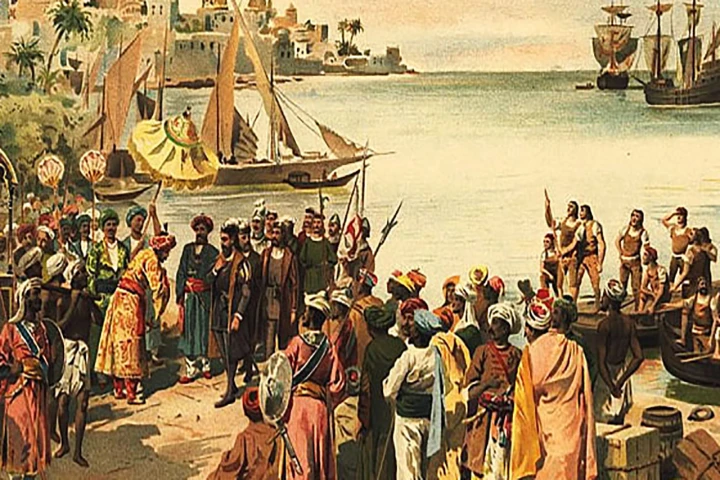

Nusantara Spices, especially Maluku's (nutmeg and clove), are a long and fantastic history about an aroma for human life. Even the sailors in the Spice Routes era excessively expressed that the scent of Maluku spices had reached them tens of miles before the sailors berthed in the spice islands. Of course, we've understood that the establishment of the imperial kingdoms of Portuguese, Spanish, British, and Dutch in Asia rooted in the search for Maluku spices. Even Jack Turner in Sejarah Rempah (2011) [Spice: The History of a Temptation (2004)] wrote that Christopher Colombus wouldn't have discovered the American continent if it hadn't been for the strong desire and lust to find the location of clove and nutmeg producer. In this sense, Jack Turner remarked that the lust for spices unexpectedly led the westerners to move in such a way. In the name of spices, richness came and went, power was established to be later destroyed, and even a new world–from the orientalists' perspective–was discovered, like the land of America and Australia. For thousands of years, the taste for spices spread all over the earth in the process of changing the world.¹

As the only place where spices (nutmeg and clove) grew, Maluku once was a paradise and destination for people from different parts of the world. The taste of paradise in various perspectives became the fundamental aspect for the explorers on taking the danger and risk of losing their lives to find the island in Nusantara. The nutmeg and clove only grew in those small volcanic islands, while there were no such plants in other places. In a book Suma Oriental, Tomé Pires stated, "The Malay merchants say that God made Timor for sandalwood and Banda for [nutmeg and] mace and Maluku for cloves, and that this merchandise is not known anywhere in the world except in these places; and I asked and enquired very diligently whether they had this merchandise anywhere else and everyone said not ".²

However, their curious feature immediately changed into greed, depicted in the colonialism, imperialism, and capitalism expressions. Aroma and taste, which became the source of heavenly pleasure for them, contrarily became the source of misery and suffering, which caused Nusantara to fall into the dark valley. Despite the explorers' ambition to dominate the precious commodities, the scarcity factor, and the high difficulty level to obtain them, spices became the prima donna for centuries.

From their native land in the small tropical and volcanic islands (Ternate, Tidore, Makian, Moti, Bacan, and Banda Neira), nutmeg, mace, and clove flowed to the Venessia, Belgium, and London markets, passing through the winding routes, circling half of the earth, brought by people from different tribes, nations, and languages. A long journey that was taken by the owners of the scent of paradise.

The Noble Banquet and the Gods' Repast

John from Hautevile in Archithrenius once wrote “Kebangsawanaan dinilai dari kemewahan sebuah meja makan dan oleh cita rasa yang terpuaskan lewat pengeluaran yang besar”. ["Aristocracy is judged by the opulence of a dining table and by the satisfied palate through a big spending"]. In fact, it is clearly pictured how spices were served in a banquet and considered luxurious, not only for the taste but also the aroma. It was seen in the Portuguese prince, Prince Henque's Banquet, on the 1414 Christmas Eve before attacking the Moors. Prince Henrique served a sumptuous banquet for the noblemen. It started with a large amount of wine, confections, sugar, and fruits, and there came the spices as the sumptuous serving, the aroma and taste of paradise that the noblemen had been waiting for.

In half a millennium distance, the spice aroma means the aroma of the aristocracy. Most of the charm came from the mystery and glamour sides, the intense effect of utopian imagination. Spices symbolized "a better life", a concept that the European nobles from the Medieval Era hunted through the ritual, wall rug, and the literature of the imaginary world. Spices could be simplified merely as a means to calculate the economic prestige, not to mention the myth that the commodity was believed to represent something exotic and magical, the sacred scent cherished by the Gods.

Long before the evidence that spices were consumed, the commodity had been used in religious and mystical behavior. Commonly, spices were burnt in incense or tossed into the fire in the temple's charcoal fireplace during the process of the religious ritual. Or else, spices could be material for fragrance and ointment rubbed on the worship statue. Exotism, scarcity, and the mysteriousness of spices became the characteristics that were aligned with the ancient worship ritual. Another enchantment was, of course, the aroma that if it was mixed with incense, the strong fragrance would burst out and strengthen the effect from various rubber and sap from the Near East and Arab, and the function still applies today, as Turner said that paganism is basically identic with smells. In addition to big festivals, the scent of spices, incense, and fragrance also sink into the whole ancient religious ritual as religion infiltrated life itself. Besides the Pagan Gods, it seemed that Roman Gods also fancied spices. When Hercules thanked the Gods in Seneca's poem upon his glory, he commanded that the finest offerings be served along with Indian spices, which means Nusantara spices brought through India.

In his writing "Between East and West; the Moluccas and the Traffic in Spices up to the Arrival of Europeans", R.A. Donkin explained in detail and separately the use of spices in India, China, and Arab. Concerning the use of clove and nutmeg in India, Donkin quoted the book Caraka Sahita–the oldest medical work composed in the first century BC–explaining that nutmeg and clove, along with betel mixed with camphor, were supposed to be chewed in the mouth to produce fragrant breath.

Clove, nutmeg, and sandalwood were used in a couple of sacred ceremony preparations. The second work that reported clove was Susutra Samhita. The treatise explained that clove, nutmeg, and camphor (without betel) were a mix of medical ingredients to dispel bad breath. In Kalidasa's period, clove was in fact, known to grow in the East islands (Dvipantara). The fragrant plant was used in a great amount in the ancient India period to the Medieval era. On average, the ingredients were used as perfumes, cosmetics, and medicines in flour, solution, syrup, pasta, powder, oil, and pastille. In the book Bhratsamhita (around 550 AD), Varahamihira served a review about perfume preparation. Nutmeg, along with camphor, was used to revive the fragrant.³ It explained the exoticism of spices' aroma that marked the typical fragrance of Indian noblemen and the sacred fragrant in the belief ritual.

Meanwhile, on average, China took various types of spices from Indonesia, and the most dominant among them were nutmeg and clove. China used cloves as medicine ingredients in the III century during the Han Dynasty. Chau Ju-kua (1178-1225) reported that clove was first brought to China by Yueh. Clove was used as a pharmaceutical ingredient in China. Like India, which used clove for medicines, China also supplied clove for pharmaceutical needs.⁴

Meanwhile, R.A. Donkin explained the news about clove usage in the Middle East–covers Persia–as: Clove in Arab is caranful, and Al-Kindi used it in the XIX century in his work The Chemistry of Perfumes and Medical Formulary (Aqrabadhin). The Arab and Persian world knew Maluku clove after a direct encounter with the spice center in Maluku. The process occurred during the spread of Islam to Nusantara in the VII century. The Maluku clove and nutmeg report in the Arab and Persian world emerged in the Al-Idrisi report about Geography in 1154. Subsequently, the report since the X century supported the statement that the scent of Maluku spice was used considerably in Maharaja Islands, what the Arabs called zabay, known as Sumatera (Sriwijaya) and the south of Malay Peninsula. In addition, Al-Mas'udi's report from 956 remarked that the kingdom exported clove, nutmeg, and sandalwood. The following report from Wasaf in 1300 and Ibnu Battuta in 1350 stated that clove was taken from Mul Java (Java Island). Malay products shipped by Arab traders to the East normally traversed the ports in India or Srilanka and were sold there. Therefore, the West Asian and South European importers simply inferred that spices came from India. In 850, Ibn Masawih placed clove, nutmeg, and sandalwood among the secondary aromatic (afawih). Maluku spice also appeared in Kitab Zat Kimia from 870 by Al-Kindi. Consequently, Arab and Persian traders used the Maluku clove supply for pharmaceutical needs and seasonings.

Referring to R.A. Donkin's explanation, it's clearly seen that clove had been a commodity traded by the Asian traders in the ancient Asian trade network before the European popularized it.⁵ The finding of black peppercorn stuffed in the Egyptian Pharoh Ramses II's nostrils and various kinds of spices in his belly, not long after his death on July 12th, 1224 BC, indicates that spices were not merely related to corpse mummification, but it was also related to the belief system of the Egyptians at that time. In the Egyptian belief system, death isn't the end of life, and thus the body must be preserved, so it will not be infected by what is called "keringat set". If the body is infected by it, death will be eternal, meaning that there will be no other life after death in this world. In this case, the fragrance of spice symbolized the glory of life upon death, the existence of eternity, like the immortal Gods, are divine–and smell like the scent of spices.⁶

The Romans, both Christians and Pagans, basically inherit the tradition from Egypt. In an area once known as Galia, in 476 to 750, the Merovingia Franka Dynasty apparently could use spices for embalming. Gregory from Tours, who lived from 538 to 594, wrote about the holy Queen Radegunda, who was embalmed with spices, in which the tradition lasts and becomes the typical funeral of the royal family members. In handling bodies after death, the core focus is not on the body preservation to look alive, but it is based upon a reason of the sacred scent, where the fragrant of spices presents as evidence of God's help or symbolic evidence of an honored status. Lying down among spices has the same meaning as lying down among the sacred scent of the angels.⁷ Apparently, not only is it used in one's death tradition, but spices, including nutmeg, mace, and clove, are also made holy symbols for the dead.

In addition to funeral rituals and death, spices were also used to protect living human bodies. In the Medieval mindset, spices had the same meaning as medicine. When spices became the popular taste, and the characteristics of the scent received multiple responses, all people agreed that the scent was sensual, spices possessed the characteristic of the scent of paradise. The desire to get spices from the native land encouraged the big investors and the Spanish and Portuguese royal parties to fund Christopher Columbus, Vasco da Gama, and Fernando Magelhans, each with a pretty big fleet. Apart from it, aside from the Islam traders, the Chinese, Indian, Malay, and Jewish traders also dominated the spice trade network. Indeed, we must admit that during the spices' journey from the East to the West, the middlemen with different cultures and religions would frequently increase prices, so when it eventually arrived in Europe, the price reached 1000% and even higher. The aura of luxury, danger, distance, and doubled profit emerged with this price.

However, aligned with the exploration, which later changed into a spice trade monopoly competition in the Eastern world, spices slowly transformed themselves from the noblemen's snacks into something that infiltrated the Europeans' lives. In further development, spices lost their magnetism. Even when the East India Company (EIC) and the Dutch East India Company (VOC) brought spices to Europe in a large amount, some of them presumed that spices were the taste of the past, the Medieval taste. The plunge of the commodity was parallel with the more congested international market competition.

The expansive development of monotheistic religion, namely Islam, also shifted the spice's position in the ritual and mystic world. Spices known as holy smoke symbolized the scent of God, marked by the incense burning with spices, or the corpse embalming using miscellaneous spices slowly began to be left behind by the majority religion. In the XIX century, with the discovery of formaldehyde and the development of the arterial embalming process by Dr. Frederick Ruysch, the practice of embalming using spices was declared obsolete. Although a small part of the world, including India and China, still undergo incense burning along with spices, the pharmaceutical subject developed far more empirically and statically in European and American medical schools. In this case, the world has become less dependent on herbal medicine, including spices.

Losing existence is not the same as losing exotism, reconstruction, and revitalization of the spice history continuously activated, as if reopening the people's collective memory about the spice glory. Like what Susanto Zuhdi said in "Menggali Ulang Sejarah Rempah" ["Re-excavating the History of Spices"] in Kompas daily, "Our luck is that the Europeans remarked the search of spice history in Nusantara, and the losing country is the one who remembers, but not records. We can't let us lose because we're lulled in the romance of memory but forget to act." The exotic of the spice aroma will never change; what will change is the actualization of the use. If the aroma was very identical in the medieval era with the high-class economic prestige and Gods' scent of paradise, today, the scent of spices will embellish the perfume and aromatherapy industry. The aesthetic market of spice aroma opens widely with the use of a synthetic ingredient that loses devotee, aligned with the human knowledge upon the danger it causes. And thus, Mark Pendergrast concluded the history of Coca Cola, by showing the copy of the leaking formula from the most popular and symbolic soft drink, which is apparently concocted using cinnamon and nutmeg.⁸ As reported by The Guardian, Thursday, June 17th, 2021, a radio announcer "This American Life" commented that the 130-year copy of a recipe of the Coca Cola owner stored in an anti theft safe in Sun Trust Bank, Atlanta, Georgia, the United States of America. Coca Cola recipe uses cinnamon, nutmeg, and coriander, known as Nusantara spices. In fact, Nusantara spices still have become a popular taste today. A secret that is carefully kept, both the trade route and the existence in the secret recipe of the capital corporate's most renowned carbonated drink globally.

______

¹ Jack Turner, Sejarah Rempah: Dari Erotisme sampai Imperialisme, Jakarta: Komunitas Bambu, 2011, hlm.16.

² Armando Cortesao, The Suma Oriental of Tome Pires and the Book of Francisco Rodrigues, London: The Hakluyt Society, 1944.

³ R. A. Donik, Between East and WestL the Moluccas and the Traffic in Spices up to the Arrival of Europeans, Philadelphia: American Philosophical Society, 2003, hlm.53.

⁴ Ibid, hlm. 156-157.

⁵ J.C. Van Leur, Perdagangan dan Masyarakat Indonesia: Esai-Esai Tentang Sosial dan Ekonomi Asia, Yogyakarta: Penerbit Ombak, 2018 hlm.144-160.

⁶ Jack Turner, Op Cit, hlm.153.

⁷ Jack Turner, Ibid, hlm.159-160.

⁸ Jack Turner, Ibid, hlm.321.

______

The article is one the top 10 winners’ works in the Bumi Rempah Nusantara untuk Dunia Writing Competition 2021. The article has gone through an editing process for publication on this page.

______

Writers: Sri Untari and Bimasyah Sihite

Editor: Doni Ahmadi

Translator: Dhiani P.

Sumber gambar: shutterstock, ekysanti23/Twenty20