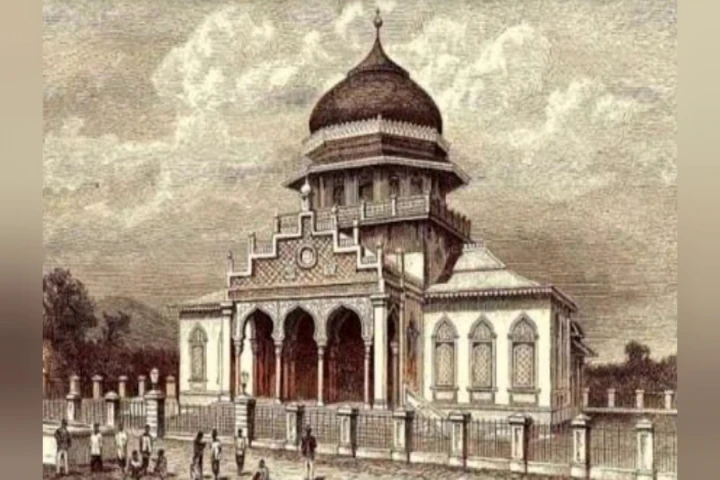

Samudra Pasai is very much associated with the first Islamic sultanate in Indonesia. It is inseparable from the history subject we got at school. As a result, the other sides of this sultanate, such as trades and economics, become invisible.

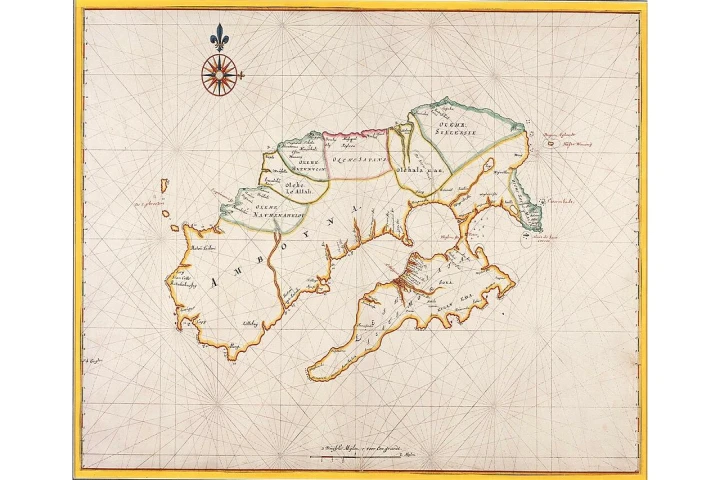

During the voyage, the estuary or other places on the coast became super strategic locations. While people counted on ships and boats as the primary long-distance transportations, seas and rivers benefited them by connecting one area to another. Samudera Pasai was one of the sultanates which were located in the estuary.

Uka Tjandrasasmita in “Pasai dalam Dunia Perdagangan” stated that Samudra was a village (gampong) at that time. It was located around 15 km from Lhokseumawe, the capital of North Aceh Regency. Samudra Village was then known as Samudra Pasai when it turned into a sultanate in the 13th century.

Further, in Suma Oriental, Tome Pires stated that Pase was the capital of the Samudra Pasai Sultanate. However, some people preferred calling it Camotora (which most probably referred to the word Samudra). The Samudra Pasai Sultanate consisted of several big cities and had numerous inhabitants.

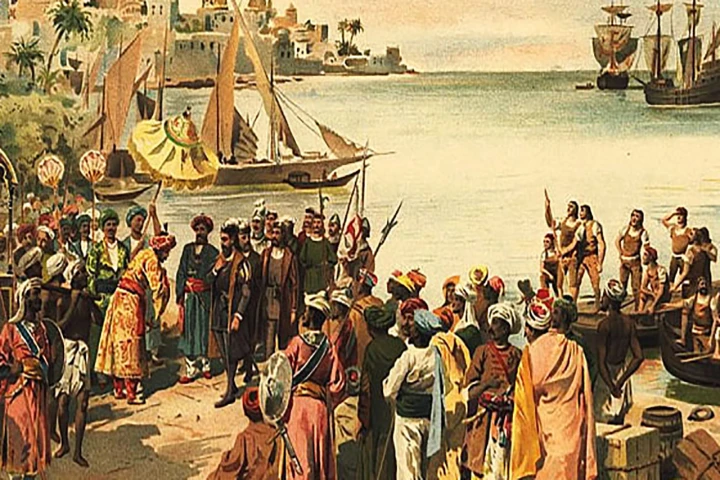

Located at the edge of the Strait of Malacca, Samudra Pasai was exposed to the international world. Various nations came and went to trade to Samudra Pasai as the stopover in the long-distance route from India, the Arabic Peninsula, or Africa. It even took place in the first centuries AD. In its development, the Europeans then took part in the Malacca trade, including Samudra Pasai.

Chinese’ journals show that Samudra Pasai was a port city that became a sailing and trading destination. In J.V. Mills research entitled “Chinese Navigations in Insulinde About AD 1500” published in Archipel Vol. 18, Chinese sailors often visited the route around the Strait of Malacca; Berhala Island, (Tanhsiii), Aru (Ya-lu) Ujung Peureulak (Pa-lut-ou), circled Chishii-wan tou, Tanjung Jambuair, and Samudra Pasai (Su-menta-la).

From Samudra Pasai, they started to sail again towards the We Island (Ch ‘ieh-nan-mao) direction and would meet the ships which sailed from Masulipatam and Quilon along the track from We Island to Lambri (Nan-wu-li). From We Island, they headed to the northern part of Rondo island (Lung-hsien-shu) to go through the western part of Sri Lanka and western part of Asia, also to the northwest—Bengal.

To welcome the travelers, Pasai ran a beach market located not far from the port. Both culture and economy went dynamically there. Numerous traders, both local and international, traded their commodities. However, imported goods were commonly traded rather than local goods.

The comers sold various goods, like fabric, cita, and porcelain. In return, the locals offered fish, salt, rice, sugar, coconuts, silk, barus, and other local commodities. Besides the Indians, traders from all over Nusantara also traded spices. Moreover, to obtain agricultural commodities which the hinterland people mainly produced at a low price, such as vegetables, fruits, and palawija, the comers could also come to the hinterland markets. Uka Tjandrasasmita suggested that the markets were not far from the central government and villages.

We can see the differences that the types of the traded goods could mark the types of related towns’ economic base. Thus, for example, the economic base of the coastal towns was trading, while the hinterland was based on agriculture.

Concerning the quantity, Tome Pires told a story about pepper export that was up to 8.000-10.000 bahar every year. The equivalent works this way: if one bahar is around 350 kg or equal to the weight of a Nile Crocodile, therefore, Samudra Pasai could sell 2.800 to 3.500 tons every year. Further, Pires suggested that the quality of Samudra’s pepper was not better than cochin pepper. It was not too big, more concave, less durable, and most importantly, it lacked fragrance.

It was told that there was a currency called ceiti. The coin was made of tin with the ruled king crafted on it. However, the international currency was commonly used, such as drama (it probably refers to dirham) and Portuguese cruzado. Nine dramas were equal to one cruzado. Using the exchange rate of $1 = Rp14.610, one cruzado valued between $160-$1,000 or around Rp2.300.000-Rp14.610.000. Therefore, the price of one bahar of Pasai pepper was less than the Malacca’s that reached 12 arratel (0,4025 kg) cruzado.

Like other kingdoms around the Strait of Malacca, Samudra Pasai also applied customs duty for exported goods. In Pires’ note, every exported bahar was taxed one maz (around 1/16 tael or 23 gram). In addition, the tax applied to ships berthed in this sultanate depended on the type of the ship or Jung.

As for foodstuff, they were not taxed, except for gift-giving. However, imported stuff from the west was taxed 6 percent, and for every slave sold five maz from gold and all exported commodities, either pepper or other stuff, they were taxed one maz for every bahar.

Trades brought a significant impact on the growth and development of the kingdoms across the coast, including Samudra Pasai. The sea trade encouraged the growth of a nation, kingdom, or coastal town, for the local rulers would build their ports to serve the needs of international traders. Further, this kind of kingdom also became the cultural gate in maintaining an active relationship with outside areas and a place where people met. Thus, it was not surprising that Samudra Pasai was more cosmopolitan than the hinterland kingdoms.

_______

Sources:

Armando Cortesão, The ‘Suma Oriental’ of Tomé Pires: An Account of the East, from the Red Sea to China, 2 vols. (Ottawa: Laurier Books Ltd, 1990).

Uka Tjandrasasmita, “Pasai dalam Dunia Perdagangan” in Susanto Zuhdi (ed), Pasai Kota Pelabuhan Jalan Sutra: Kumpulan Makalah Diskusi. (Jakarta: Departemen Pendidikan dan Kebudayaan RI, 1997), 28-42.

_______

Text: Endi Aulia Garadian

Editor: Tiya Septiawati

Translator: Dhiani Probhosiwi

Image: Ministry of Education, Cultural, Research, and Technologi of Republic of Indonesia