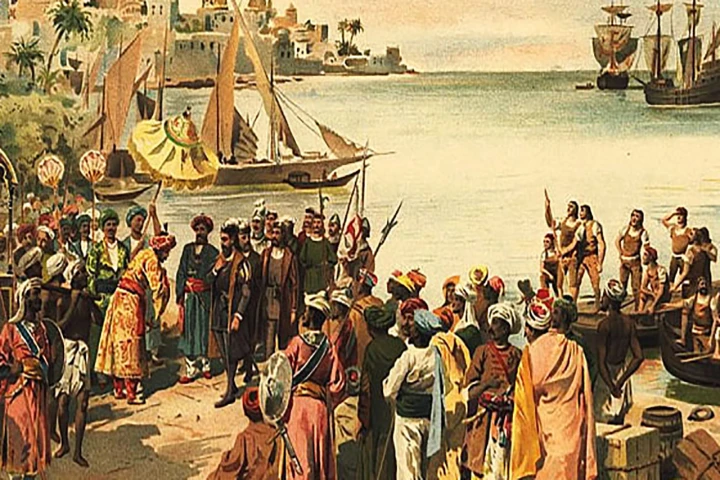

Since the 15th century, Nusa Ambon became the cosmopolitan stage where many countries gathered, interacted, and traded. Knaap (1991) stated that Ambon was a migrant city where people came to find fortune. If the Spice Routes can be understood as a cultural route (ICOMOS, 2018), the cultural development in Nusa Ambon can't be separated from the strategic position in the shipping route and spice trade. Various nations interacted and exchanged cultures in Ambon. Although there was an incompatibility with the local culture, on the other hand, it enriched Ambon's culture. Cultural diversity can be understood comprehensively if it is seen from the universal cultural elements (Kroeber & Kluckhohn, 1952). And, one of the elements is language.

As a result of the historical process, the Ambon language has a different character from the Malay language in other areas, like Malay Manado or Ternate. Besides acculturating with the local language, the Malay Ambon language also absorbed foreign vocabulary from Portuguese and Dutch. It wasn't surprising that Collins (1975) stated that the Ambon language was a creole language formed and influenced by various countries.

The history of the Malay Ambon language has long been studied. Collins (2005) and Muhammad (2018) pointed out how the Malay language became the Nusantara language, including for the people of Ambon. Abdurachman (2008), Da Franca (2000), and De Castro (2019) saw many Portuguese vocabularies absorbed by the Ambon language. It’s not surprising that Russel Jones (2017), Kustiyanti (2014), and Sri (2016) managed to identify the Dutch loanword in Malay and Indonesian languages, so Van Minde (2002) managed to identify 321 Dutch vocabulary in the Ambonese language.

Unfortunately, the study is partial, and it hasn't seen the development process of the Ambonese language comprehensively. The writing will narrate the language-cross in Nusa Ambon historically.

By using library research, the primary literature was served to be read and made into a historical narration. In the trade period in the 15th to 17th centuries, the maritime cities in Southeast Asia were connected. After the fall of Srivijaya, the trade hub was consecutively replaced by Pasai, Malacca, Jhor, Patani, Aceh, and Brunei. Malay became the primary trade language in Southeast Asia in the trade network. It affected the figure and role of Malay people. The people of Malay were often associated with cosmopolitan traders in Southeast Asia.

They possessed the same identity–speak in Malay and were Muslims. They had a Malay identity with the same language and religion, although their ancestors might be Javanese, Mon, Indians, Chinese, or the Philippines (Reid, 2011:10). Nusantara traders spoke in Malay as they talked in their language. Malay also became the official written language in palaces and religious institutions. Further, at the same time, the Malay language was used daily, including for trade and social interaction in the market and ports (Collins, 2005:32). In this relationship, the Malay language greeted the Spice Islands, including Ambon. Uniquely, the Malay language was mixed with the local language and created what is now called the Ambonese language.

On the one hand, the Malay language enriched the linguistic treasure for the Ambonese. However, the domination of the Malay language used in daily communication seriously affected the existence of local languages there. In several regions, parents didn't pass down the mother tongue to their children. As a result, as time went by, the Ambonese Malay language replaced the local language and developed into the mother tongue for the ethnic groups there. The position of local languages became weaker. Local languages may become extinct. Further, if it is ignored, Ambonese or the people of Maluku will lose their identity (Muhammad, 2018: 109-110).

The interaction between Portuguese and Ambonese didn't erase the position of the Ambonese Malay language. On the contrary, it allowed the Ambonese language to absorb Portuguese vocabulary. The interaction between the Portuguese and Ambonese occurred when they traded. They often made a trade deal with the local chiefs. When they first arrived in Hitu, they were welcomed by Jamilu Prime in Hila. Jamilu Prime was very respected and given the title Kapten Hitu by the Portuguese. The word Portuguese "Capitao", which means Captain, is used to call Jamilu Prime. The locals then used it with the local accent Kapiten. Besides trading, the Portuguese spread Catholic missions. Therefore, some vocabulary is related to religious affairs, such as gereja [church] from "igreja". As the colonial ruler, some colonial officials were named after Portuguese vocabulary, such as algojo from "algoz" (Abdurachman, 2008; Da Franca, 2000; De Castro, 2019).

Several Portuguese loanwords can be found in Ambonese toponym, such as (1) Gang da Silva; (2) Poka; (3) Cova; (4) Cabo de Marthafons; (5) Barranco; (6) Pagar Noodwyk; (7) Sungai Olifante; (8) Jalan Kayadoe; village names of (9) Leke, (10) Asilulu, (11) Passo, (12) Hatalai; and (13) Batu Capeo. The Ambonese absorbed Portuguese vocabulary to name an alley (Lorong Da Silva); oceanic trench (cova); land ownership (Pagar Noodwyk); coral reef (Batu Capeo); river (Sungai Olifante); cape (Cabo de Marthafons); village names (Poka; Leke, Asilulu, Passo; and Hatalai); and street names (Jalan Kayadoe). The vocabulary refers to the result of interaction between the Portuguese and Ambonese in the 16th century. The mixed marriage between them also fastened the cultural encounter in the context of creole language.

In Ambon, the locals named their alleys based on their origin. For example, if the Da Silva descendants inhabited an alley, they named their alley Da Silva Alley. The locals also copy how the Portuguese call various geographical phenomena like cova for oceanic trench; pagar noordwyk for the land ownership; Batu Capeo for a stone shaped like a hat; Sungai Olifante for river shaped like an elephant; Cabo de Marthafons for the memory of Martim Afonso de Marthafons (Wijaya, dkk, 2020).

The name of villages in Ambon borrowed many words from the Portuguese. Some of them are Asilulu, Passo, and Hatalai. The people of Asilulu are the first Ambonese who met the Portuguese in Nusa Telu. The people of Asilulu also introduced them to the Empat Perdana. Another village, like Passo, also witnessed another episode of the Portuguese's arrival in Ambon. The Portuguese lived in Passo when they were expelled from Hitu. Interestingly, the Ambonese remember one of the Portuguese Captains in Ambon, João Caiado de Gamboa, naming one of their streets Jalan Kayadoe. In the episode of the Portuguese's arrival in Ambon, they were expelled by the Dutch. Some Portuguese families did not want to move and chose to serve the Dutch. They stayed and married the locals. They even changed their religion. They lived on King Soya's land and were known by the Dutch authorities. People believe that they lived in Hatalai and Naku, where their descendants can be found today (Abgurachman, 2008; Da Franca, 2000; De Castro, 2019). The Portuguese also used the Malay language to spread the Catholic religion. Francis Xavier, a Jesuit missionary who arrived in Malacca from Goa in 1545, also learned the Malay language. He translated the Catholic and Basic Catechism prayers into the Malay language. In Maluku, especially Ambon and Morotai, Francis Xavier taught religious doctrine using the Malay language, which was easier to understand. At that time, the Malay language was used and understood extensively (Collins, 2005:33).

Along the 16th century, by imitating Xavier, the Malay language became the medium of instruction to spread Catholicism in Southeast Asia. The Portuguese, Spanish, Italian, and Dutch missionaries also used the Malay language in their church mission in Maluku. An Italian priest wrote a Catechism in the Malay language in Ambon. However, the work was never printed and only written in handwriting. Unfortunately, not a single manuscript in the Malay language produced by the missionaries during the Portuguese era can be found today. Therefore, documentary evidence from the Malay language used by the missionaries during the Portuguese period hasn't been discovered (Collins, 2005:34).

When time changed and the Dutch managed to expel the Portuguese, the Ambonese Malay was used as the medium of instruction in schools, churches and the translation of several books of the Bible. The Bible which has been published in the Ambonese Malay are Rut, Yunus, Lukas, the Story of Apostles (Yesus Pun Utusan-utusan Pun Carita), Tesalonika, Timotius, Titus, and Pilemon. The Dutch missionaries translated the Bible in Malay language and brought it to Ambon. The Dutch even intervened with the residents to memorize the Bible and then baptized. They were guided in Ambonese Malay and forbidden to use the local language (Muhammad, 2018:53).

In everyday life, Dutch was used as an administrative language and became the primary language for the colonizers. However, the Malay language functioned as the primary language for the Ambonese. Interestingly, people in the village still used their local languages (Muhammad, 2018: 111-2). It's reasonable that later, Hitu's political elite spoke Malay fluently. Imam Rijali was one of them. In his refugee period due to the Dutch's brutal attack in the middle of the 17th century, he managed to compose Hikayat Tanah Hitu. The story was written as the suggestion from Karaeng Pattingalloang, a nobleman from Makassar (Collins, 2005: 49). Inevitably, the 17th century became the golden era for the Malay language and literacy development (Fand, 2011). Many kingdoms in the Malay world sent their letters in the Malay language. One of the examples is a letter from the Governor of Ternate, Kimelaha Salahak Abdul Kadir bin Syahbuddin to Ambon and Seram, which was sent to East India Company (EIC). The letter aimed to ask for England's help to expel the Dutch (Collins, 2005:51).

Ambonese also borrowed many Dutch vocabularies to name things in domestic life. For example, they call "rim" that refers to belt; "fork" that refers to fork; "trap" that refers to stairs; "Frangen" that refers to catch; and "lopas" that refers to run. Ambonese also absorbed Dutch vocabularies to call family relations between them. They use the loadword "oom" for uncle; "fader" for father; "muder" for mother; and "tanta" for aunt. Dutch vocabularies were also borrowed to describe human's quality, such as "dol" for crazy; "sterk" for strong; "swak" for weak; "onosel" for stupid; and "flauw" for weak. It also applies to animals and plants' names, such as "kasbi" for cassava and "kakarlak" for cockroach. When they're outside their homes and walk along the roads, the Ambonese often call "oto" that means car; "strat" for street; and "standplaats" for bus stop. To say thank you, the Ambonese also borrowed Dutch vocabulary, "dangke" (Van Minde 2002; Muhammad, 2018).

Another interesting thing is that many street names in the Netherlands were taken from the warriors of Indonesia’s independence and human rights activists. They are Trimurtistraat, Pattimurastraat, Diponegorostraat, Diponegorohof, Maria Ulfahstraat, Soekasihstraat, Roestam Effendistraat, Tan Malakastraat, Soewardistraat, Munirpad, Martha C. Tiahahustraat, Kartinistraat, Mohammed Hattastraat, Chris Soumokilstraat, Sjahrirstraat, and Irawan Soejonostraat (Rundjan, 2015; Pamungkas, 2019). Among the warriors, there are two Ambonese: Pattimura and Martha Tiahahu.

________

Bibliography

Abdurachman, P. (2008). Bunga Angin Portugis di Nusantara: Jejak-Jejak Kebudayaan Portugis di Indonesia. Jakarta: LIPI Press

Collins, J.T. (1975). The Ambon Malay and Theory of Creolization. Kuala Lumpur: DBP

Collins, J.T. (2005). Bahasa Melayu Bahasa Dunia Sejarah Singkat. Jakarta: Yayasan Pustaka Obor

Da Franca, A.P. (2000). Pengaruh Portugis di Indonesia. Jakarta: Sinar Harapan

De Castro, J.M. (2019). Lautan Rempah Peninggalan Portugis di Nusantara. Jakarta: Kompas Gramedia

Fang, L.Y. (2011). Sejarah Kesusasteraan Melayu Klasik. Jakarta: Yayasan Obor Indonesia

ICOMOS. (2008). The Icomos Charter on Cultural Routes. Accessed through https://www.icomos.org/quebec2008/charters/cultural_routes/EN_Cultural_Routes_Charter_Proposed_final_text.pdf

Jones, R. (2017). Loan-Words in Indonesian and Malay. Jakarta: Yayasan Obor

Knaap, G. (1991). A City of Migrants: Kota Ambon at the End of the Seventeenth Century. Indonesia. No. 51 (Apr., 1991), pp. 105-128

Kroeber, A & C. Kluckhohn (1952). Culture: A Critical Review of Concepts and Definitions. Massachusetts: Kraus Reprint Company

Kustiyanti, M. (2014). Kata Serapan dari Bahasa Belanda pada Bidang Kuliner dalam Bahasa Indonesia Analisis Fonologi. Isn’t Published. Depok: FIB-UI

Muhammad, H. (2018). Kodifikasi Bahasa Melayu Ambon: Studi Diversitas Historis Linguistik. Ambon: LP2M IAIN Ambon

Pamungkas, M.F. (2019). 9 Orang Indonesia yang Menjadi Nama Jalan di Belanda. Online media page Historia, published on 6 August 2019

Reid, A. (2011). Asia Tenggara dalam Kurun Niaga 1450-1680: Jilid 1 Tanah di Bawah Angin. Jakarta: Yayasan Pustaka Obor

Rundjan, R. (2015). Daftar Nama Tokoh Indonesia yang Jadi Nama Jalan di Belanda. Online media page Historia, published on 7 April 2015

Sri, A.A.P.S. (2016). Bahasa Belanda yang Terserap dalam Bahasa Indonesia. Research Report. Denpasar: FP-UNUD

Van Minde, D. (2002). “European Loan-words in Ambonese Malay”. K.A. Adelaar & R. Blust (Eds). (2002). Between Worlds: Linguistic Papers in Memory of David John Prentice. Canberra: Pacific Linguistics

Wijaya, D.N., D.Y. Wahyudi, S.Z. Umaroh, & N. Susanti. (2020). “The Portuguese Loan-Words in the Toponymy of Ambon ”. Paper was presented in INUSHARTS 2020

________

The article is the first winner’s work of the Spice Routes writing contest 2021. The article has gone through the editing process to be published on this page.

________

Daya Negri Wijaya is a lecturer in the Department of History, State University of Malang.

Editor: Doni Ahmadi

Translator: Dhiani P.

Image: Dinas Pariwisata Provinsi Maluku