The Inuit dialect of the Eskimo language—in the North Pole—has over 50 words to explain a word that in other languages in the world has only one word, "ice" or "snow". Let's see four examples: kriplyana 'snow that shows up in the morning', intla 'snow that has drifted indoors', bluwid 'snow that's shaken down from objects in the wind', and tlun 'snow sparkling with moonlight'. There's also a word to explain the falling snow, snow in the process of melting, and many more.

In another context, English has only one word: rice, to explain the seed, rice plant/paddy, rice [cooked], and porridge. Meanwhile, Tagalog and other local languages in the Philippines have dozens of words to explain a word that we call rice in English. The other example is coconut. Again, there is only one word in English to describe coconut, while several languages in Nusantara have some words to describe it. For example, Taba (East Mekeang), a local language of North Maluku, say niwi toho for 'a coconut that has just come out of its flower'; niwi gao for 'a young coconut'; niwi mamala for 'a coconut in which its flesh and shell are starting to reach the perfect age'; niwi bata for 'a coconut in which half of the coir is starting to dry'; and niwi mango for 'a fully ripe coconut'.

The example of vocabularies used in a certain language in the world related to nature and typical to the language shows that every word in every language in the world depicts the scope and the civilization characteristics of the owner of the language. A certain word in the A language can be expressed in several words in the B language, and vice versa.

Words are the fundamental element of a language, and language is the cultural barrel. Every language in the world has its way of expressing the culture and civilization of the native speakers. It is one of Sapir-Whorf's hypotheses about linguistic relativity, a hypothesis formulated by two linguists, an instructor and his student in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Edward Sapir and Benjamin Lee Whorf.

Each language has its way of expressing the speaker's culture; the speaker's culture can be summarized in two areas: the cultural creation and social behavior and the nature or environment surrounding the native speakers. The interactions between those two will give rise to words and vocabularies in every language, carrying out two main tasks: to describe nature and express the nature of thoughts of the native speakers.

The Local Name of Nutmeg and Clove

If we want to say or claim a plant to be the floristic richness of a particular region, one of the ways is to find out the original name or the truly local name where the plant lives. If it is not endemic to a certain region, and the plant or the floral richness is imported from other areas, the plant's name is almost certainly borrowed from the native language where the plant is from. For example, a popular fruit in New Zealand, kiwi, does not grow in Indonesia or North Maluku. Conversely, New Zealand does not have these plants: tome-tome or gayam, or perhaps capilong, ngusu, or mujui. If only kiwi could grow in the Gamalama Hills, Ternate, we would certainly call it kiwi and not sawo. Similarly in New Zealand's shores, if ngusu 'katapang' and capilong 'nyamplung' can grow there, they would not be named kiwi pantai [the coastal kiwi].

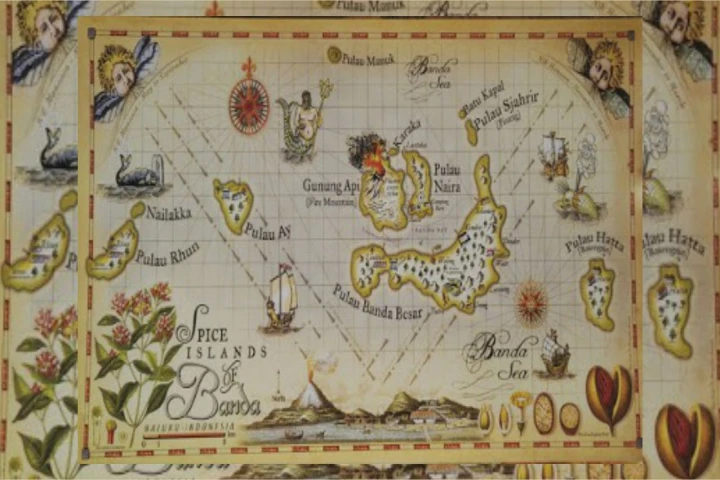

From this simple analogy, we are trying to find the logic of "the zero point of the Spice Routes" jargon from the language side. One of the possible meanings of "the zero point" is "the starting point". This "point" is certainly not a static sign or place. It is a place that gives a sign about something (an action and natural event) starts, about the start of something. The zero point shows "the starting point", "the origin".

By relying on the definition, we can define "the zero point of species" as "the beginning of a journey or the wandering of spices" all over the world in the hustle and bustle of world trade in the 16th century. Because the beginning is the origin, and the origin sticks to the authenticity, to discuss the origin of spices, we can do one method: look for the language trace by examining the name of the spices in the local languages. So let's pay attention to the list of local names of nutmeg and clove—the black gold of the 16th century—two essential spices in 16th-century world trade.

| TTE | TDR | MT | MB | WED | TOB | PAT | GAL | |

| Nutmeg | gasora | gasora | pala | asem | gasora | gasora | sem | gasora |

| Clove |

gaumedi bualawa |

gomode | odai | ada | cengke | buanga | cengke | balawa |

Note: TTE (Ternate language), TDR (Tidore language), MT (East Makeang), MB (West Makeang), WED (Weda/Sawai language), TOB (Tobaru language), PAT (Patani language), and GAL (Galela language).

There is some important information about the names of nutmeg and clove in several local languages. First, almost all local languages in North Maluku have native names for nutmeg and clove. Second, gosora is nutmeg's name for most of the languages in the list. Third, there are several name variants for nutmeg, such as (a)sem in West Makeang and Patani languages; odai~ada for East Makeang (Taba) and West Makeang (Omamoi). Fourth, the MT language does not have a native name for nutmeg and Weda as well as Patani languages do not have the native name for clove. Fifth, and this is unique/interesting; Tobaru language has its name for clove, buanga.

There are several explanations for the five things above. They are first, related to the relation of language families in (North) Maluku. In a light conversation with my colleague, Professor James T. Collin, an American linguist who researches and writes Nusantara languages, especially Malay and local languages of East Indonesia, he said that Maluku (in a cultural and historical sense, which currently administratively belongs to North Maluku) is a place where two major language families in the world "met", namely Austronesian and non-Austronesian (specifically Papua phylum). Those two major language families had encountered centuries ago. Thus, they certainly influenced and borrowed each other's vocabularies.

Second, we found two facts in the table about nutmeg and clove vocabularies for eight (8) local languages in North Maluku. The first fact is, although they came from different language families, the East Makeang (Austronesian) and West Makeang (non-Austronesian) have the same name for clove, odai~ada. The second fact, although they came from different language families, there is an intersection—maybe there was mutual borrowing—between Patani language (Austronesian) and West Makeang (non-Austronesian) in calling nutmeg, (a)sem.

Third, there are variants of clove names in several non-Austronesian languages (for instance, in Ternate, Tidore, and Tobaru languages). Ternate and Tidore languages call it a phonological variant, gaumedi—gomode, while in Tobaru language it is called in a very different name, buanga.

Ecolinguistic Argumentation

Like the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis about linguistic relativity mentioned at the beginning of this writing, words produced by a certain speech community, in addition to becoming the nature of thought's product, is also a response toward the nature of the surrounding environment. From this perspective, there is a two-way relationship between nature and human creation in language. Nature provides itself to be labeled by the speaker. Words produced are related to the ecological service—flora, fauna, and natural events.

With this argumentation, we can do a thesis, "The surrounding flora shapes the speaker's nature of thoughts to convene to create words as names to label the type of flora." Here, the native speaker, as the language creator, agreed to name every flora around them through the arbitrary convention.

If so, names like gosora, gaumedi/gomode, odai, ada, (a)sem, and buanga are responses from the native speakers of the languages over the plants they saw in nature around them. If we ask, why does the native speaker call a tree—that in the 16th century was called "black gold"—as gaumedi, odai, etc.? We can find the answer in two significant traits of language: convention and arbitrary.

The Linguistic Evidence as the Sign of the Origin of Spice

Besides the local names for nutmeg and clove, we also hear about cengkih dokiri [dokiri clove], a variant of clove which reputedly came from Dokiri Village, Tidore. Although it was planted in another area in North Maluku, on Makeang Isalnd, for instance, the variant of clove is still called cengke dokiri.

Besides the local names of nutmeg and clove, in several local languages mentioned above, the evidence of a particular variant of local clove in Dokiri is two significant proofs from the language heritage. The authenticity of nutmeg and clove names can strengthen the argumentation on the origin of these two spices which once were the most-wanted spices for the Westerners in the 16th century.

With the language evidence—or I call it as linguistic evidence—about the naming of nutmeg and clove that are the same and different in several local languages in the North Maluku, we can strengthen the argument that Ternate can truly be assigned as "the zero point city" of the world Spice Routes, especially nutmeg and clove, two famous spices in the world in the 16th century.

By borrowing the local wisdom in the Ternate language, totike rimoi toma dofu madaha, 'I seek one in a million', the discovery of the nutmeg and clove local names is a linguistic evidence that can help us strengthen the proposal of Ternate as "Ternate the Initial Point of the Spice Routes" or "Ternate the Starting Point of the Spice Routes" or "Ternate the Departure Point of the Spice Routes".

Above the argumentation and linguistic evidence, we certainly need to arrange the timeline of the "Ternate the Starting Point of the Spice Routes" proposal as the intangible world heritage by paying attention to two essential things. First, strong, argumentative academic scripts, and second, steady steps in one proposal timeline.

_______

Gufran A. Ibrahim is a professor of Anthropolinguistics, the Faculty of Humanities, Khairun University

Editor: Moh. Atqa & Doni Ahmadi

Translator: Dhiani Probhosiwi

Photo: finedininglovers.com